In the latest issue of Forum, we see how terrorist organizations raise & move funds to better understand this part of the global effort to disrupt terrorism

Understanding how terrorist organizations raise, move and use funds is a critical part of the global effort to disrupt terrorist atrocities, according to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the intergovernmental body responsible for assessing terrorist-financing risks, developing global standards and evaluating countries’ compliance.

Indeed, while law enforcement and lawmakers are key players in the battle against terrorism, financial institutions play a unique role in combating terrorist financing. Terrorists often rely on the financial sector to transfer money and many countries, including the US, require banks to perform due diligence on their customers and to report suspicious transactions.

As FATF’s website states, “Follow the money.”

The Role of Financial Intelligence

“Financial intelligence is critically important in the fight against terrorism,” says Dennis M. Lormel, founder and president of DML Associates. Lormel has been fighting financial crimes for 45 years, including 28 years as a special agent in the FBI and serving as chief of the FBI’s Financial Crimes Program.

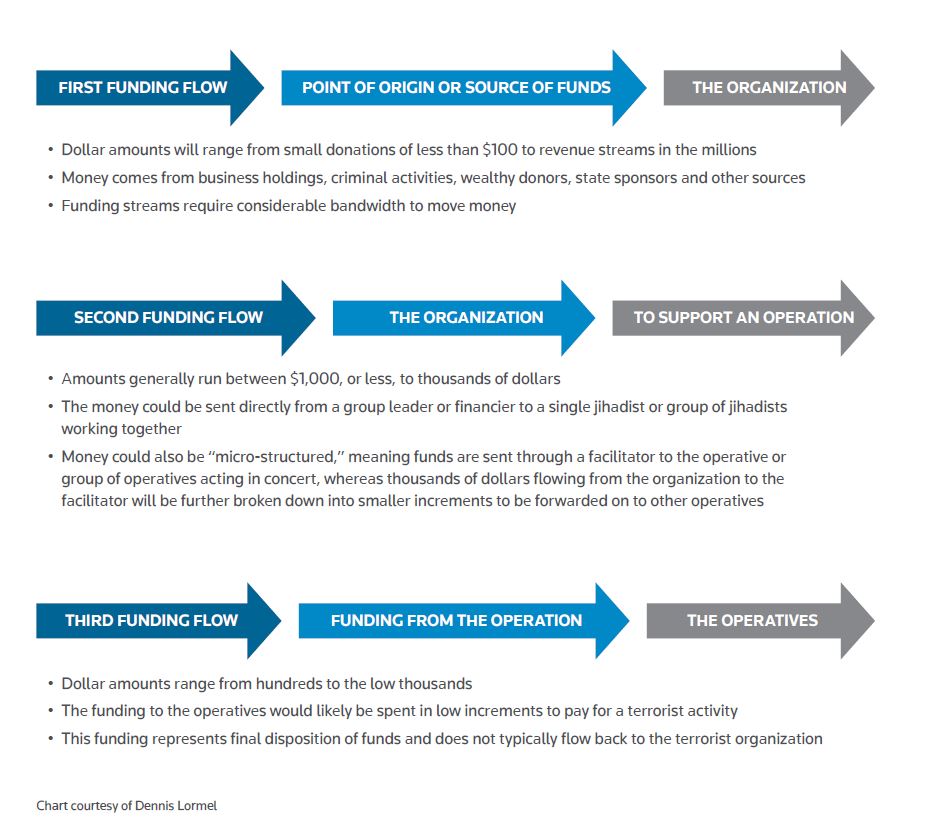

Unlike money laundering, which tends to move in a circular flow – from individuals laundering money gained by illegal activities, into the financial system and then back to the criminal – true terrorist financing is more linear, Lormel explains. Funds move from a person or group into the terrorist network and often do not come directly back into the hands of the terrorist, but instead support a wider network of terrorist activities.

“The terrorist gets an indirect benefit such as publicity for their cause, political influence and more propaganda for recruitment,” Lormel says, adding that a money launderer is motivated by greed while a terrorist is motivated by a cause.

How Do Terrorists Fund Their Activities?

Lormel says there arethree primary funding streams terrorists rely upon, although there are many variations to the three streams that terrorists can follow. The key for them is having consistent access to funds at select intervals between the point of origin and the point of distribution. Terrorist cells exercise several methods to raise and “clean” their money, ranging from illegal activities like organized fraud or narcotics, to legitimate funding sources, including charitable organizations or legitimate businesses, according to the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS).

The third funding stream can come from “disenfranchised individuals, often out of touch with reality,” Lormel says, adding these are also known as “lone wolves” or “homegrown violent extremists (HVEs).” These individuals often self-fund their own jihad through their employment income, government assistance, proceeds of criminal activity, family donations and other sources. HVEs are responsible for the source of funds themselves, as opposed to the terrorist organization raising the money for them.

Lormel believes we must establish and maintain tactical measures to thwart terrorist attacks. “This is where financial institutions, and more broadly the financial services industry, play a significant role,” he says.

How Barclays Bank Uses Financial Intelligence to Thwart Terrorists

Frederick Reynolds agrees with Lormel. As global head of Financial Crime Legal at Barclays, a former deputy director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and the former deputy chief of the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section of the Department of Justice, Reynolds is at the forefront of the fight. “Financial institutions play a critical role in the detection and prevention of money laundering and terrorist financing,” Reynolds says.

Reynolds and the team at Barclays spend countless hours creating institution-specific terrorist financing typologies, as well as researching, monitoring and preparing for terrorist attacks and ways they can proactively detect terrorist-financing schemes through studying financial transactions.

They are looking for commonalities – what is known in the industry as “white flag” and “red flag” indicators of suspicious activities, explains Reynolds. White flag activities are those that are common among terrorists, but also among the general population, Reynolds says, adding that going to a coffee shop, shopping at a hardware store or renting a truck are some examples. “How do you tell the difference between a weekend gardening trip and someone acquiring supplies for an attack?”

That’s where the red flag indicators become useful. Red flag transactions can include travel to a border region of a known terrorist state, purchasing knives before an attack or frequent domestic and international ATM transactions, according to Reynolds and organizations such as the Egmont Group, an international forum for financial intelligence units to share and collaborate information about terrorist-financing trends.

Taken holistically, and examined by a trained analyst, financial intelligence can make connections and judgments, and even alert law enforcement as appropriate. “It is art, not science,” Reynolds says. “Financial intelligence specialists can narrow down their focus as much as possible and find those people who look like they are most likely to be a foreign fighter or someone who is planning a terrorist attack,” Reynolds notes.

How Financial Intelligence Can Take Proactive and Reactive Steps

Financial intelligence pros want to get this right because there are proactive and reactive steps banks can take. Yet, often they are playing a game of catch-up. Once the terrorist attack has happened, financial intelligence units react and deploy their designated terrorist financing resource team. “We normally identify terrorist-financing reactively, after the fact, through negative news,” Lormel says. He adds that following these identified proactive steps can improve the likelihood of identifying suspicious activity before that activity evolves into a terrorist event.

Both Lormel and Reynolds agree that one crucial component of stopping terrorist-financing plots is partnering with law enforcement and using robust information sharing, as allowed by law. “Public-private partnerships are critical,” Reynolds contends. “It is the single most important thing we can do to detect and stop terrorists.”