A high-profile money laundering case in New York involving an Impressionist painting has highlighted the risks facing the art sector, just as the Fifth Money-Laundering Directive (5MLD) begins to crack the whip on European art dealers.

According to court documents filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) on December 19, U.S. accountant Richard Gaffney and German-born Harald Joachim von der Goltz must surrender one of the Règates à Henley paintings drawn by Impressionist artist Raoul Dufy (he produced 43 works with the same name) and other assets, if convicted on two counts (Counts 2 and 3) of the most recent Panama Papers indictment.

Von der Goltz plans to plead guilty to some of the 10 financial-crime counts the duo are charged with, prosecutors say. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) marked the painting for forfeiture pursuant, in part, to Count 3, which alleges money-laundering conspiracy. This forfeiture notice underscores the inherent risks of art market transactions, which John Byrne, vice-chairman of anti-financial crime consultancy AML Right Source in Cleveland, Ohio, has identified as the “inability to identify the ultimate beneficial owners.”

Small speck

The Dufy painting is just a small speck in the broader galaxy of fine art, a market that topped $67.4 billion in 2018, according to a joint report authored by UBS and art fair organizer Art Basel last March.

Tess Davis, the executive director of the Antiquities Coalition, an American non-profit organization that combats the illicit trade in ancient art and artifacts, said the art world is a “black hole” when it comes to Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) compliance. “Billions of dollars move through auction houses each year,” Davis said. “Who knows the names of the real sellers?”

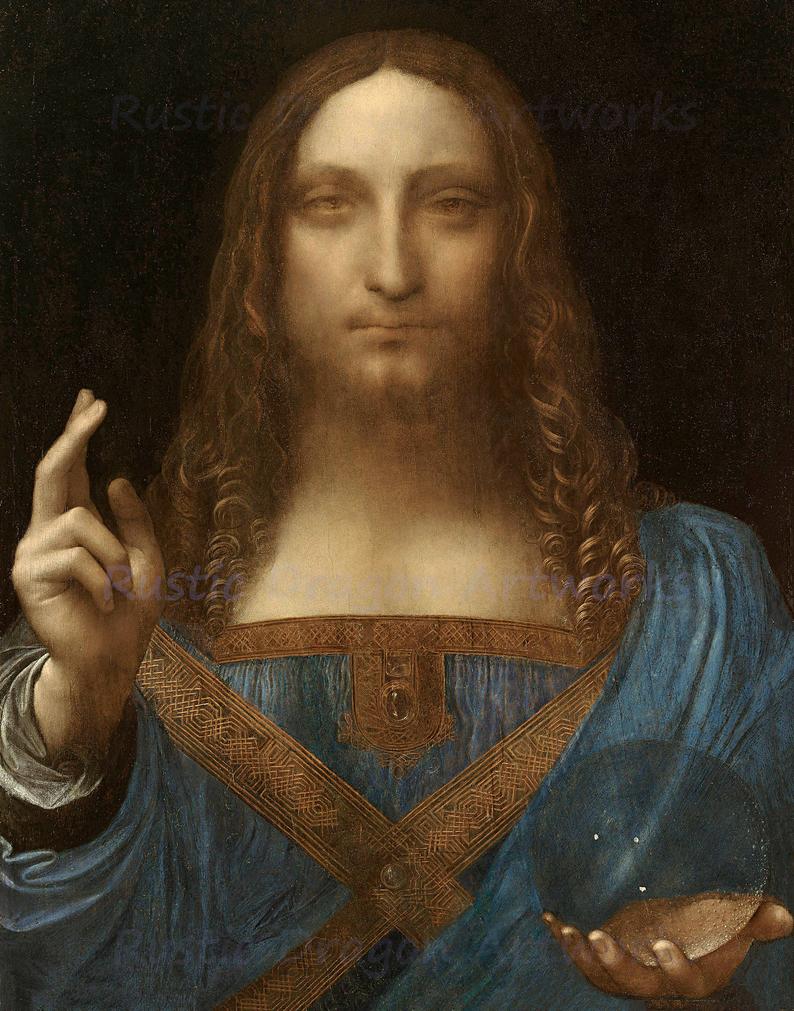

Perhaps no transaction constellates the art market’s anti-money laundering (AML) event horizon more than the 2017 sale by Christie’s of Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, for $450.3 million. The current ownership and whereabouts of this painting are unknown.

Art Miami

The prevailing theme that emerged at Art Miami, an industry fair held in December, was that art market AML controls were much stronger in Europe, which implemented sweeping 5MLD legislation this month, than in the United States, where there is no BSA reporting requirement for fine art dealers or collectors.

In the U.K., one London dealer said that his art gallery’s corporate intelligence adviser, Elizabeth Deheza, performs due diligence on all prospective buyers. The most liquid works of art are the most vulnerable to laundering, added the gallerist. “With the new laws coming into force, traders and intermediaries will soon have to comply with enhanced due diligence checks on transactions over 10,000 euros,” Deheza said in an email.

Under 5MLD, all European art dealers and intermediaries now have to obtain official documentation to identify their clients for all art transactions totaling 10,000 euros or more.

Perhaps no transaction constellates the art market’s anti-money laundering (AML) event horizon more than the 2017 sale by Christie’s of Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, for $450.3 million. The current ownership and whereabouts of this painting are unknown.

Deheza also downplayed art AML risks in general. “Money laundering is more commonly seen with assets that are harder to trace and forge” like diamonds, said Deheza. “Where we do see risks is in charitable donations to art institutions, undeclared conflicts of interests between various parties in a transaction, and after 5MLD there will be a regulatory non-compliance risk too.”

Swiss “freeports”

Beyond transactions at galleries, auction houses, and art fairs, there is significant AML risk in so-called freeports, which are duty-free storage warehouses for artwork, antiquities, and other tangible assets. Some of the most well-known freeport havens include Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Singapore.

In Switzerland, more than $100 billion worth of property is housed in the 600,000 square-feet storage space that encompasses the Geneva Freeport alone, according to the 2017 Panama Papers book, Secrecy World, by investigative journalist Jake Bernstein.

Freeports pose a major obstacle to UBO transparency, said Kim Manchester, managing director of ManchesterCF Financial Intelligence, a Toronto-based firm that provides online financial intelligence training to financial institutions and public-sector agencies. For further layers of anonymity, freeport customers can create offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands or a similar secrecy-favorable jurisdiction and rent a vault under the company name. These shell company schemes present a problem for AML enforcement because even the latest Swiss AML laws have gaps that enable businesses to avoid disclosing the identities of their UBOs to reporting authorities.

Thus, these AML safeguards fail to deter professional money-laundering organizations from appointing various nominees, who could be installed into control roles to obscure the true identities of adverse UBOs, Manchester said. For banks, the risk of the freeport laundering can be best characterized as part of the larger category of “trade-based money laundering,” he added.

Banking art businesses intelligently

With more intense focus from regulators on art market AML gaps, bank compliance officers need to become more vigilant in their oversight of the diligence controls employed by their art business customers.

From auction houses, to galleries, to private-wealth clients using legal entities to execute transactions, financial institutions should look to the due diligence standards introduced by the Responsible Art Market, a Geneva-based non-profit organization. According to its 2018 Art Transaction Due Diligence Toolkit, the highest-risk transactions include art bought and sold by politically exposed persons and those “which occur entirely via non-face-to-face means or which are unusually complex.”

Manchester noted that the change in regulations may do little to ultimately disrupt illicit practices in the art world. “It’s going to be very difficult to catch the professional money launderers because they have been working in an opaque art market for generations,” he said.