Is the Am Law 200 useful in terms of being a "category" whose members exhibit particular shared characteristics vital for analytical purposes? We think not

This 3-part series was written by Bruce MacEwen and Janet Stanton of Adam Smith, Esq.

In our reflections on the release of the 2020 Am Law 200 data, we began with our basic instinct to think in terms of averages. In summation, we said: Don’t do it.

Now, we will challenge a different premise: That the Am Law 200 is a useful category.

“category, n., a class or division of people or things regarded as having particular shared characteristics.”

In the most trivial sense, of course the Am Law 200 is a category, in that its members are the i) 200; ii) U.S.-based; iii) law firms; that are iv) ranked highest in terms of 2019 gross revenue. And the greatest share by far of reporting and commentary on the Am Law firms is premised on looking at the 200 as a whole (or the Top 100, or the second 100). But for analytical purposes, are those useful categories? We think not.

To begin to explain why we say this, let’s step outside of the Law Land bubble and look at another very familiar gross-revenue based firm ranking, the Fortune 500. Here are the most recent Fortune 10 companies: Walmart, Amazon, Exxon Mobil, Apple, CVS Health, Berkshire Hathaway, UnitedHealth Group, McKesson, AT&T, and Amerisource Bergen.

Now answer this: What — the tautology of revenue aside — do these firms have in common? You might counter that Walmart and Amazon are both retailers, but could their strategies and their business, revenue, and operating models possibly be more different? (Half of Amazon’s profits come from their cloud-computing platform, not retail sales.) And let’s not even start with Exxon vs. Apple.

Managing and leading one organization that brings in $1.5 billion or more is a lot more similar to leading another firm of similar scale than it is to leading a firm that’s 1/10th of that size…

Here’s an even more striking thought: Coincidentally, a brand-new lineup of Ford’s F-Series pickup trucks is launching this summer, the first complete revamp in six years. Auto junkies out there know that the F-Series has been the best-selling vehicle in the U.S. by far since, well… forever. How big a deal is it for Ford to get this launch right?

-

-

- The F-series generated about $42 billion in revenue last year, not far behind the iPhone’s $55 billion.

- That was more revenue than the four major professional sports leagues (MLB, NHL, NFL, and NBA) combined.

- As a standalone company, the F-series would be solidly in the Fortune 100, ahead of companies like McDonalds, Nike, Coca-Cola, and Starbucks.

-

Why are we talking about a pickup truck in an article on the Am Law 200? Simply to make the point that when you see a “class or division of things” ranked by revenue you need to begin probing a lot harder.

Shall we perform a similar dissection of the Am Law? Here are the top 20 Am Law firms: Kirkland & Ellis; Latham & Watkins; DLA Piper; Baker McKenzie; Skadden Arps; Sidley Austin; Morgan Lewis; Hogan Lovells; White & Case; Jones Day; Gibson Dunn; Norton Rose; Ropes & Gray; Greenberg Traurig; Simpson Thacher; Weil Gotshal; Mayer Brown; Sullivan & Cromwell; Davis Polk; and Paul Weiss.

Are all 20 of these firms plausible substitutes for one another in the eyes of clients? For every kind of matter, no matter how high-profile? How low-profile? If not, to what extent are all 20 really competing head to head? And if they’re not (really) competitors, to what extent does it make sense to lump them all into the same market or into the same category?

Size matters

That said, managing and leading one organization that brings in $1.5 billion or more is a lot more similar to leading another firm of similar scale than it is to leading a firm that’s 1/10th of that size (See the Am Law #170 firm, for example, with annual gross revenue of $150 million).

This isn’t just our opinion.

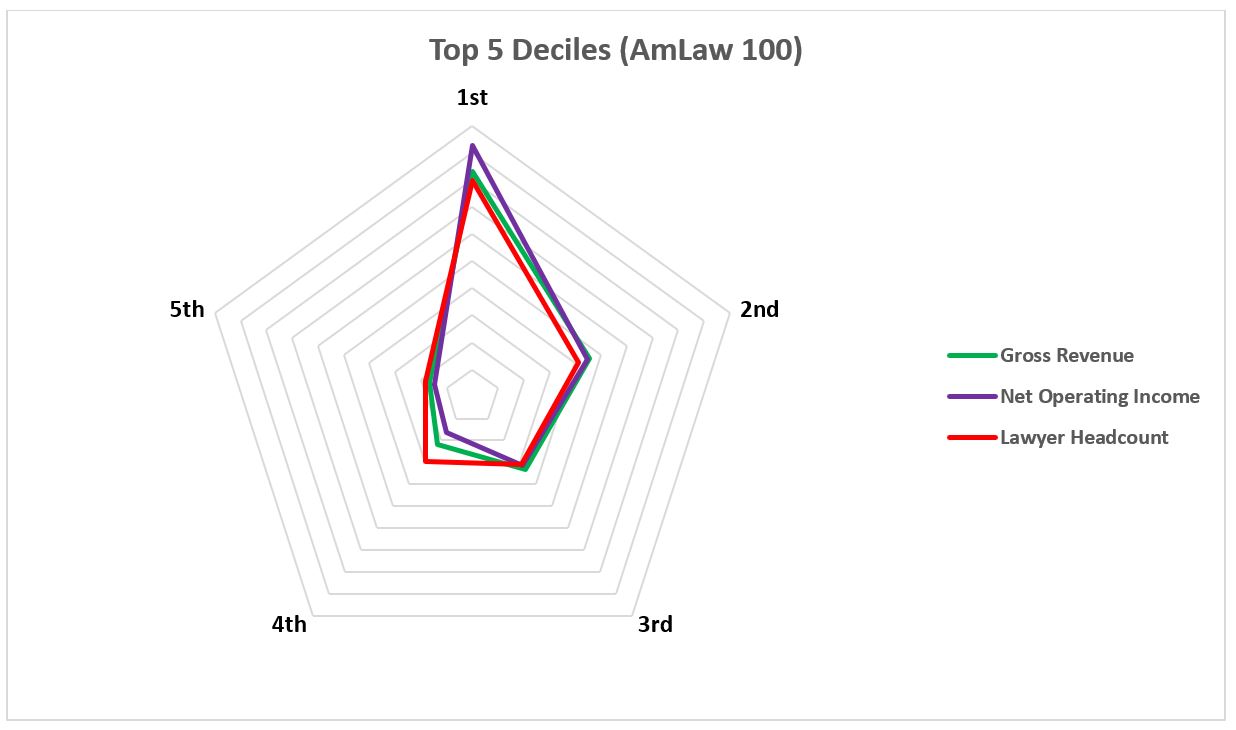

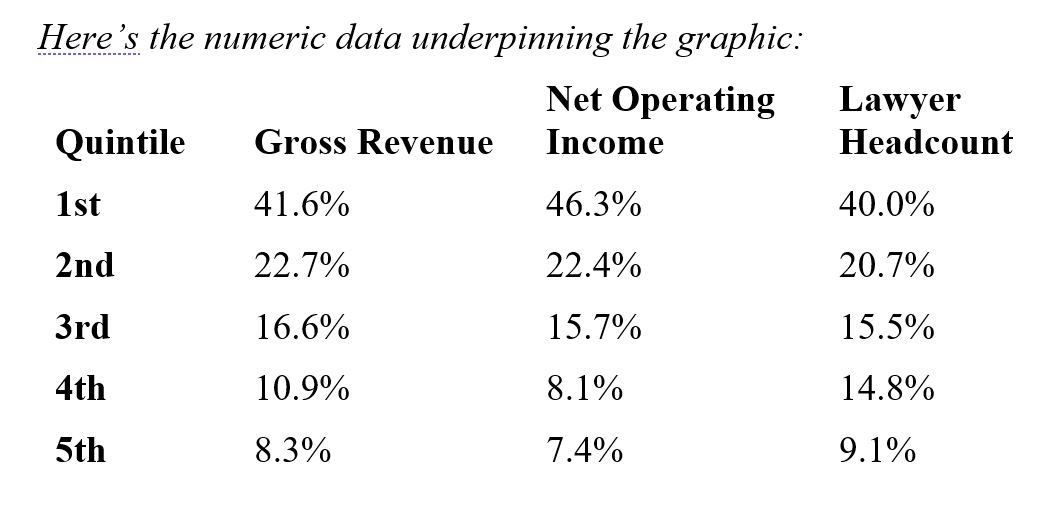

When we started looking at the 2020 data more closely, an odd anomaly emerged. It became apparent when we zeroed in on the Am Law 100 by quintile, and specifically at the distribution of i) gross revenue; ii) net operating income (NOI); and iii) lawyer headcount in each quintile. (In our first installment in this series, we sliced the full list of 200 by decile, so put that out of your head for a moment.) We selected these three data series, out of all the series the Am Law 200 provides, both because all are very important metrics for a law firm and, candidly, because they are hard for firms to cosmetically adjust.

To be specific, for the 20 firms in each quintile we compared what percentage share that quintile represented for the Am Law 100 totals for each of the three data series. So, for example, the formula for the top quintile’s share of total revenue: (Top 20 share) = (Sum of Top 20 firm’s revenue) ÷ (Total revenue of the Am Law 100).

Here’s the odd pattern we found:

-

-

- For the top quintile, the share of total NOI across all 100 firms > the share of revenue > the share of lawyers.

- And the fourth quintile is the exact opposite: Its share of NOI < its share of revenue < its share of lawyers.

- (The second quintile is like the first but less so, the fifth like the fourth, but less so, and the third comes in pretty much even-steven on all three measures. We’ll address this in a minute.)

-

Graphically, it looks like this:

All else being equal, one would expect the shares of each data series across each quintile to be the same. Your lawyer headcount should correlate with your revenue, which should correlate with your NOI.

The fact that the first group of firms is so anomalous requires some plausible explanation.

Our hypothesis is this: The business models of the top 20% of firms generate a disproportionate share of revenue from fees based on bonuses, the investment-banking pricing model (percentage of deal value), success premiums, and so forth, rather than from the plain old billable hour, compared to the other quintiles. Despite the differences among those top 20 firms in prestige, geographic footprint, practice mix, historic path, and all the rest, they are without question extraordinarily capable organizations that can bring massive resources to bear on any legal matter — fast and at global scale.

You can critique law firms’ blind adherence to conformity and rejection of even the most incremental change all you want — and we do — but this data points to a truly impressive capability. When that’s what a client needs, a “premium” may be rather beside the point.

In the meantime, do you still think the Am Law 200 is a meaningful analytic category?

In our third and final installment of this series, we will go back to unearth the past decade’s historical record of the Am Law data and see whether this phenomenon existed in the past and whether it has changed over the years. Stay tuned.