Artificial Intelligence – AI for short – is a topic of hot debate. Some technologists foresee AI threatening to bring about the end of professional practice. For example, the UK-based news resource, LegalFutures, predicts that technologies automating the work of associates, herald the collapse of law in less than 15 years. The report claims: “the firms that will be most affected would be the very large, high-value commercial firms whose associates expect to be given interesting work and many of whom aspire to the status and wealth that equity partnership affords.”

Many professionals, on the other hand, see some level of change, but nothing so dramatic as threatening the very existence of the profession. A recent study by McKinsey & Co estimates that 23% of lawyer time is automatable. Similar research by Frank Levy at MIT and Dana Remus at University of North Carolina School of Law concludes that just 13% of lawyer time can be performed by computers.

The fact that a debate is occurring is itself telling. No similar predictions were attached to any prior technology. No one claims that matter management, knowledge management or legal process management will bring down law firms.

AI in practice

An assessment of the impact of AI requires an understanding of both the practice of law and technology. While the referenced studies evaluated activities of lawyers and current technologies, they do not sufficiently engage future states of technology.

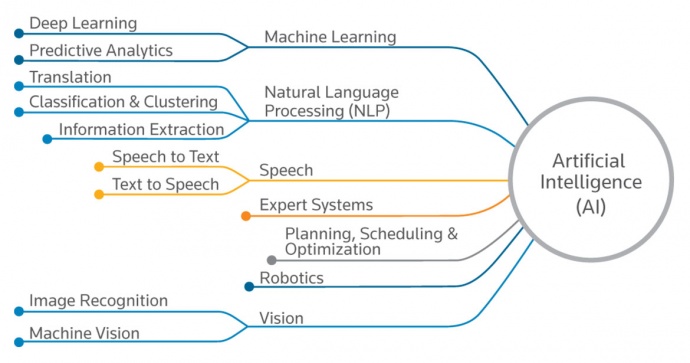

Predicting future states of AI is no easy task. AI defies simple definition. As illustrated by Michael Mills of Neota Logic, it is comprised of many different sub-specialties. Broadly, they can be grouped:

- Cognition tools (to capture and synthesize text, voice and images)

- Unsupervised deep learning tools (to find relationships through neutral, hierarchical and stacked networks)

- Supervised tools (to understand meaning and context through classification, extraction and semantics)

- Learning tools (to apply and extend understanding through machine learning and predictive analysis)

- Optimization tools (to apply information to specific questions through expert systems)

Deep learning tools work well in unsupervised situations, where the software operates without human oversight. Systems look for patterns, relationships and connections in unstructured data. For example, a deep learning system may analyze images, automatically classify them and make connections. They might identify a photo of an animal as a zebra, determine through geotagging that zebras are found in Africa and zoos, and then connect this data with all the information on the World Wide Web.

In the professional realm, most AI systems rely on some form of human supervision.

This oversight may be provided in the form of taxonomies, exemplars or iterative training procedures. In our work of contract analysis, we apply three main technologies. First, structural classification determines how contracts are organized, what clauses they contain, the standard language for each clause and the full range of deal-specific alternatives. Second, data extraction captures key contract language (such as the extract language of a grant of license) and key business terms (including names, places, dates and amounts). Third, natural language captures context and meaning identifying subject matter, actions and objects.

When will AI solutions become mainstream?

Despite advances, there is, of course, some way to go before AI becomes mainstream. While we may not know the exact schedule, we do know how we will get there. It will be in three stages, already well underway.

Stage one is to find the relevant material. In learning a new area, we need access to source material. We need to find relevant cases or prior contracts. Today, we are less likely to go to the library or form file. This stage is automated. We use a computer to find the sources. The key technology applied in this stage is search.

Stage two is to review the material and identify the relevant elements: the relevant issues in the case, or the relevant elements of a particular transaction. This is how we learn over time: by reading many examples. Today this step is augmented with legal analytics.

Stage three is to determine the optimal outcome. What is the best argument to make in a case? What is the best structure of a transaction? This capability, on the bleeding edge of automation, is the focus of “big data” and expert systems.

The progression mirrors the skill stages of professional experience. Moreover, each stage commands a greater share of the overall value of legal services. The first stage is the domain of contract attorneys and librarians, and has already been highly automated. The analytic stage is largely the domain of junior attorneys. The final stage is represented by the judgment and skills of experienced lawyers. Even if technology is not able to achieve the highest levels of practice, the financial rewards of legal analytics are greater than all prior legal technology markets.

Percentage of impact; speed of change

The impact on the profession, and its ability to respond, depends on two factors: percentage of work susceptible to automation and speed of change. As Clayton Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma thesis asserts: If the portion of legal work that is capable of automation is closer to the lower estimates and innovation is introduced over a long period of time, the changes will likely be absorbed by an evolving practice. But as the percentage of change and the speed of innovation increases, the greater the risk to the status quo and the greater the opportunity to the innovators.

Your views of the future can be assessed through two questions:

Do you believe that drafting of pleadings and contracts can be automated through the creation of standards?

Do you believe that legal analytics can effectively review precedent to identify common elements and patterns, namely the issues in a litigation matter or the elements of a business transaction?

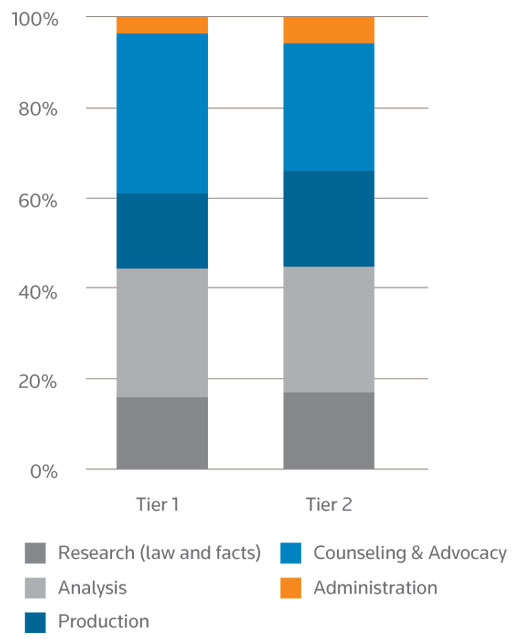

Lawyer task by percentage of time

The chart applies the same data as the Levy-Remus study, but the data funnels into broader categories: namely, research, analysis, production, counseling, advocacy and administration. If AI is limited in its major impact to document review (a small segment of fact research), then as Levy-Remus contend, technology will have a marginal effect. If, on the other hand, emerging technology can automate some or all of the tasks of analysis and production, the impact will be far greater. In all likelihood, the next stages in the evolution of the profession will not be one or the other of these polar extremes. The next few years will likely favor lawyers who can use partial states of automation to outperform their peers. Indeed, the fastest growing sectors in the legal market are legal process outsourcers and managed legal service providers employing both efficient processes and technology to capture work from traditional legal service providers.

About the author

Kingsley Martin is a founder of KMStandards and has developed software capable of automatically analyzing legal agreements and creating contract standards. Martin has more than 30 years of experience in practice of law, software design and development, strategy and management.

Kingsley Martin is a founder of KMStandards and has developed software capable of automatically analyzing legal agreements and creating contract standards. Martin has more than 30 years of experience in practice of law, software design and development, strategy and management.

Learn more

Demystifying artificial intelligence can be done in seven simple steps. To learn more about AI and its impact on the legal industry, visit LegalSolutions.com/ai.

Demystifying artificial intelligence can be done in seven simple steps. To learn more about AI and its impact on the legal industry, visit LegalSolutions.com/ai.