As many law firm leaders cast their eyes toward the horizon, their thoughts inevitably turn toward how they can best navigate the choppy waters of a changing economy

Law firms have been adept at finding opportunities in even the most challenging economies, whether that means increasing work related to bankruptcies or successfully competing for newly price-sensitive clients.

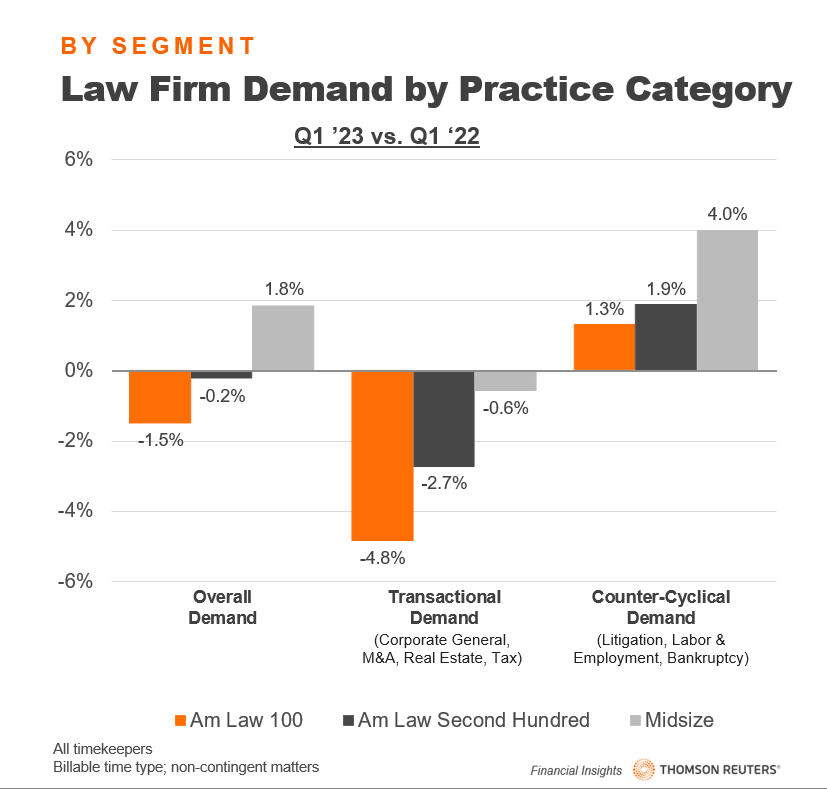

In this current era of economic instability, it’s becoming clear that not all firms can ride the waves so easily. And while there are uncertainties in the economic outlook, there are also signs that any pain will not be shared equally. In the first quarter of 2023, for example, Midsize law firms have seen their demand grow by 1.8%, yet the larger Am Law 100 firms have seen their demand contract by 1.5%, a sharp reversal from that sector’s banner results in 2021.

Even in the current lukewarm economy, transactional work has declined significantly from its 2021 heights, and counter-cyclical work is starting to pick up. Transactional demand at the largest law firms was down nearly 5% over the past year, mostly due to contraction in mergers & acquisitions and real estate work. These practices were relatively strong at this time last year when interest rate increases were just beginning. The Am Law Second Hundred has fared slightly better, with firms there seeing a 2.7% drop in demand in these practices; but again, the beneficiaries are Midsize firms, which only saw their transactional demand dip by 0.6%.

Demand for counter-cyclical practices — defined as litigation, labor & employment, and bankruptcy — is accelerating. Litigation and labor & employment have been relatively strong since the third quarter of 2022, but Q1 2023 is the first quarter that they’ve began really driving growth.

Again, these practices are not contributing to growth evenly across all sectors. Within the Am Law 100, demand for these counter-cyclical services is only up 1.3%, while at Midsize firms it has increased by 4%. In all three segments, litigation has been particularly strong.

These figures paint a picture that implying a strong correlation between firm performance and the current state of the economy. This may not be a shocking revelation, but it certainly implies that law firms’ fortunes in the latter half of the year are closely tied to the fortunes of the economy as a whole. The problem for many firms is that the economic outlook for the rest of 2023 remains uncertain.

A clouded economic outlook

Since the onset of the global pandemic, the U.S. economy has been surprisingly resilient. However, even the most optimistic lawyer can’t help but notice signs of weakness, such as continued high inflation and rising interest rates, relatively high rates of public debt, and ongoing geopolitical instability.

Recently, concern about the general health of the economy has been compounded by realizations about the fragile state of the banking sector. While most lawyers currently in practice have experience with various flavors of economic slowdown, a national banking crisis — as is well-remembered from the experience of 2007 and 2008 — is another matter entirely.

“To the extent that banking becomes more fragile, law firms could be at risk,” says Lawrence White, the Robert Kavesh professor of economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business. “The other side of banking fragility is that if a law firm has a banking practice, that’s probably going to expand.” White also points out that if there are more bank mergers, that will also generate additional legal work. “My general feeling is demand for legal services by high-quality law firms is going to remain strong.”

To better understand the health of the economy and the state of the banking sector, you should start with Silicon Valley Bank, where 90% of deposits were uninsured, White explains. That made the bank a bit of an outlier — but he notes that nationwide, more than 40% of deposits are uninsured and those deposits are held by a skittish 1% of banking customers. Anything that makes those customers even more nervous could trigger a scare such as the ones that affected not just Silicon Valley Bank but First Republic Bank and Signature Bank as well.

Indeed, there are three areas that are most likely to create further unease, says White: Commercial real estate, interest rate risk on the part of banks, and inflation.

Commercial real estate — With many firms’ return-to-office status in constant flux, weakened office occupancy could mean that those who own office buildings, and the banks that lend money to them, could be under strain. That strain won’t be felt immediately; instead, it will build as commercial real estate loans are rolled over and renewed, or, in the worst-case scenario, when building owners declare bankruptcy. At that point, the banks that hold those mortgages will need to take losses, which could unnerve still-skittish depositors.

Interest rate risk — In 2021 and 2022, banks bought long-term treasury bonds and long-term mortgage-backed securities at relatively low interest rates that still yielded a margin over deposits. With higher interest rates, those securities are now under water. Both bank analysts and uninsured depositors realize that will eventually affect banks’ balance sheets, especially if interest rates don’t come down.

Inflation — Of the three risks cited by White, inflation is the one he described as being most prominent in the popular debate about the economy. White says he’s “an optimist and I tend to think we’re probably past the worst of our inflation difficulties,” Recent news has been encouraging — U.S. headline inflation grew only 3.0% in June, well down from its heights and close to “normal” levels. But of course, there’s no guarantee this progress will continue if not reverse.

The surprising success of Midsize law firms

The success of Midsize law firms, compared to their larger peers, could indicate that their clients are seeking lower billing rates as general economic pressure persists. While other research has shown that large law firms are getting remarkably little pushback on their rates — even amid all the market chatter about it — a less-obvious type of pushback may be evidencing itself in other, less direct ways. Rather than balking at a firm’s bill or negotiating with an Am Law 100 firm directly, some clients may be sending more work to Midsize firms instead. In some practice areas, at least, the cost savings offered by Midsize firms may compensate for any perceived difference in quality.

In an economic slowdown, it appears that the largest law firms would have the most to lose. So far, they have been able to increase their work rates, which has somewhat masked the slump in demand. But inflation affects law firms just as it does other businesses, and the recent success of Midsize firms suggests that larger firms may not be able to raise their work rates at such a rapid pace much longer. While the hourly rate may appear to continue to climb, White anticipates that actual billing may take a hit. “They’re not going to decrease their rate,” says White of the Am Law 100, “but in informal conversations, they’ll throw more things into the package when they talk about what those bills will look like.”

Of course, that strategy only works as long as compensation increases, and inflation remains moderate. In the event of a protracted slowdown or a return to higher inflation levels, large law firms may find themselves in an unexpected competition with their Midsize peers — one in which brand and perception matter, to be sure, but where fees become uniquely important.

For more on the economy with NYU Prof. Lawrence White and Thomson Reuters Analyst Bryce Engelland, check out the latest episode of the Thomson Reuters Institute Insights Podcasts here.