Alternative legal service providers (ALSPs) recently have become the Talk of Law Town. But how big is the ALSP market, actually?

Coverage of ALSPs’ doings is everywhere you look, ranging from the breathless “Did you see how much money XYZ firm scored in its latest round?” to just-the-facts recaps of start-ups, mergers and acquisitions.

Into this, Thomson Reuters has released its third biennial survey of the sector showing that since reporting began in 2015, independent (“purpose built”) ALSPs have grown by more than 70% and the entire ALSP market now brings in $14 billion annually, which is broken down further by type:1

-

-

- independent ALSPs, with $12 billion in revenue (86%)

- the Big 4 at $1.4 billion (10%)

- captive law firm offerings at $480 million (3.4%)

-

The relatively insignificant share of the captives — in terms of our “dead end” hypothesis — matters not. This market is nothing if not young, and its future stretches before us.

The business case for law firms launching their own so-called captive or in-house ALSPs seems to follow a classic go-to move for mature incumbents potentially under threat from disruptive new entrants – steal the upstarts’ thunder. Copy, clone, steal, fast-follow, whatever you care to call it: Offer ALSP-style services yourself under your trusted brand name and using your massive “installed base” of clients, professionals, offices and networks.

And it can work. Remember the Browser Wars, when Microsoft® responded to first-mover Netscape Navigator by releasing its own Internet Explorer (IE)? Bothersome and frankly inconsequential antitrust charges aside, Microsoft is stronger than ever, whereas Netscape began hemorrhaging market share scarcely a year after its launch when IE was released. Eventually, Netscape and its browser faded into obscurity.

Copy, clone, steal, fast-follow, whatever you care to call it: Offer ALSP-style services yourself under your trusted brand name and using your massive “installed base” of clients, professionals, offices, and networks.

This tactic can also fail. Under perceived threat from discount air carriers Frontier and JetBlue, two major air carriers launched their own low-cost brands in the mid-2000s. United’s was Ted, and Delta had Song. Both lasted just a few years before being shut down and their aircraft reabsorbed into the mother fleet.

What made the difference? Embedding new features into an operating system is a core Microsoft competence; so, to launch IE, the good ship Microsoft had to change its DNA not one whit. By contrast, consider what Delta and United were up against in running a no-frills airline: Both major airlines had to design, launch and operate an entirely different business model under their original roof; different route map, pricing structure, flight operating manual, separate workforce with its own distinct pay scale, aircraft configured in new and incompatible ways, and not least, a different customer base. This proved too much to sustain.

What went wrong? After all, Ted and Song were both airlines; it wasn’t as though Delta and United had to learn how to fly an airplane all over again. Likewise, captive ALSPs can talk a good game; but in the end, it’s all legal services.

And, to quote one unidentified leader at a law firm captive: “Law firms should win this battle if they can become hybrid law firms embracing a broad range of traditional legal services and alternative services under one umbrella.”

Our friend here has a point. Captive ALSPs work in theory, but just not in practice. Launched into the market, they run smack into Ted and Song realities.

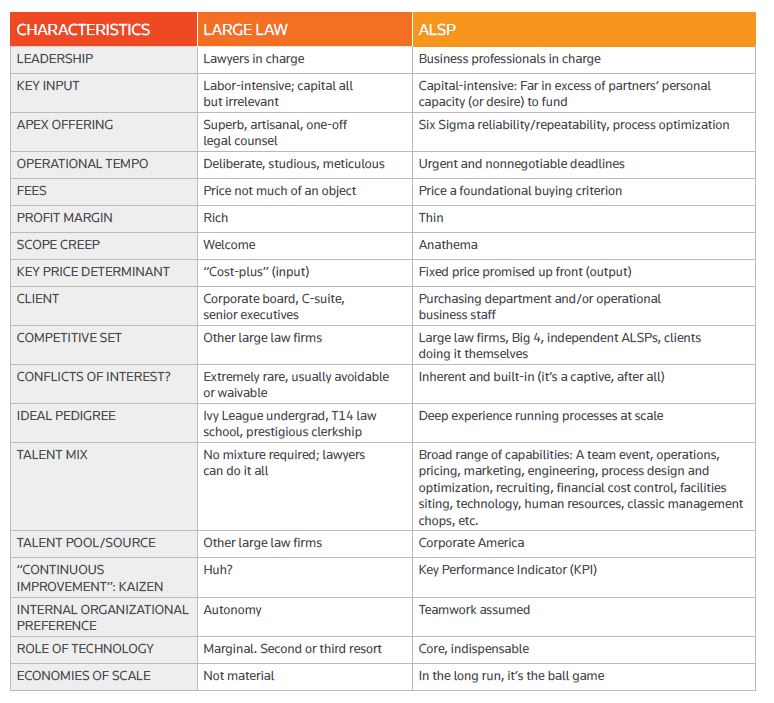

To understand how a thoroughly rational strategic response to market disruption can founder on the shoals of organizational dynamics, let’s scrutinize the internal organizational changes a large law firm would have to adopt to give its captive ALSP a chance to succeed.

If your firm proposed launching an ALSP – captive or otherwise – who would you want on your management and leadership team? And what would you look for among your supporters?

Given the business imperatives outlined above, you would need people comfortable with making a long-term investment requiring substantial capital even before revenue begins to flow, in a venture with no guarantee of success, who are therefore patient and will be understanding of midcourse corrections, and where lawyers have no role at the head table.

Clearly large law firm partners fit this profile to a T. Said no one, ever.

Don’t Just Take Our Word for It

Alex Hamilton, a former Latham & Watkins partner in London, launched Radiant, his now-thriving ALSP (called a NewLaw player on that side of the pond) more than a decade ago; and, in a recently published retrospective on his experience, he said that “traditional law firms aren’t optimized for cooperation, they are optimized for autonomy of partners” and “partnership models are perfectly designed to protect the current power structure and resist change, with the most successful under the old model holding the reins.” (Not incidentally, the thrust of Hamilton’s piece is why he could not have launched Radiant within and under his former umbrella.)

The point is whether any of the captive ALSPs have changed the law firm. That is the acid test of success.

Mark Cohen, a co-founder of Clearspire (an early NewLaw entrant, now sadly shuttered) and a widely read commentator in the legal world, knows the lawyer personality well and put his finger on the challenge they would face heading an ALSP. “Most lawyers believe it’s better not to make a mistake than to be creative in solving a problem,” Cohen explains. Hamilton’s view shines a spotlight on the gale force headwinds that captive ALSPs face from their very own backers and core constituency. It scarcely matters whether the captive succeeds in meeting its aspirations, or even, frankly, whether its operations prove competent and fit for purpose. The host is, sooner or later, going to reject the foreign graft.

For evidence, we pose a question to you: Despite all the fanfare accompanying the launch of prestigious BigLaw’s shiny new ALSPs, how much do you hear about them two, three or five years later?

The point here is not whether some, or even all, captive ALSPs continue to operate at some peripheral level – it’s embarrassing to shut down a new initiative, and I would wager if that has happened it’s a safe bet it would not have been announced to the media. Rather, the point is whether any of the captive ALSPs have changed the law firm. That is the acid test of success.

After all, you don’t launch a captive ALSP in hopes of beating Axiom or UnitedLex in the marketplace. Realistically, captives’ addressable market is confined to work deemed suitable for ALSPs that the mother firm throws off. So, no captive will succeed if the measure has any relationship to market share or revenue.

There are exceptions, of course. For example, Littler Mendelson has so thoroughly incorporated process optimization, repeatability and a component parts architecture into its production and delivery of legal services that it is, indeed, seamless. Littler’s ALSP-like processes are embedded within and inseparable from everything else it does. In other words, Littler is a different firm than it was before it embarked on these initiatives. Such examples are rare, however; and a successful captive has to fundamentally reform how its large law mother ship delivers legal services and meets its clients’ expectations. We’re now past the first century birthday of the Cravath System, and it’s still lawyers all the way down. As long as that’s the case, captive ALSPs are a dead end.