Law firms are constantly faced with a difficult, high-stakes task of evaluating current lawyer performance, potential lateral hires, and fresh graduates, and heading into the hiring season, this issue becomes especially relevant

Selecting the right running back or tight end for your fantasy football team is no easy task, and often is one filled with uncertainty. One pre-season miscalculation, or freak injury, could derail your entire fantasy team’s trajectory and stop you from achieving undying glory. While fantasy football stakes may be high, the stakes are even higher for law firms.

Recently, at the third annual Legal Value Network Conference Experience (LVNx), several industry experts discussed driving change in the legal industry and other pressing issues for law firms today and in the future. My team and I had the opportunity to present on a topic we consider extremely important and forward-looking: evaluating lawyer productivity.

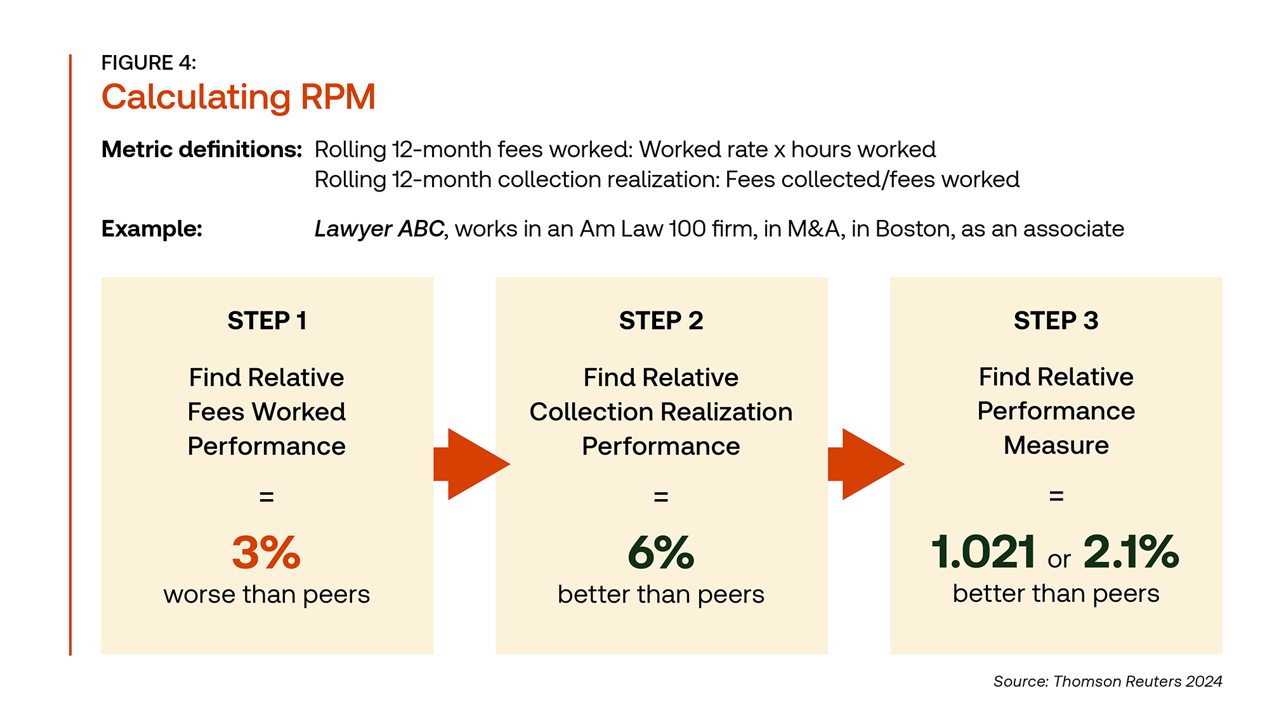

A month ago, the Thomson Reuters Institute released the Relative Performance Measure (RPM) report, describing on a new metric for measuring lawyer productivity. The RPM report detailed the theory, motivation, and potential application of the RPM metric, which finds a timekeeper’s relative performance in fees worked and adjusts it for their relative performance in collection realization.

To offer an example, RPM evaluates an associate in an Am Law 100 firm, working in M&A in Boston, by comparing that associate to similar associates in the same law firm segment, location, and practice area. In the graphic below, we can see that this associate’s performance in generating fees is 3% below replacement level, while their collection realization is 6% above. After adjusting for these factors, their final RPM score is 2.1% above replacement level. Essentially, RPM is a profit-focused metric that measures an attorney’s relative output, rather than their total hours worked, providing a more comprehensive assessment of their economic impact.

To further the discussion, we created a workshop under the framework of a fantasy football-style draft, in which the audience and general managers (GMs) selected between two lawyers instead of professional football players. We enlisted four GMs and split them into two teams. Each round, we presented two anonymized lawyers from the Thomson Reuters Financial Insights dataset, provided productivity and demographic-related statistics, and asked the audience to debate and then choose their pick.

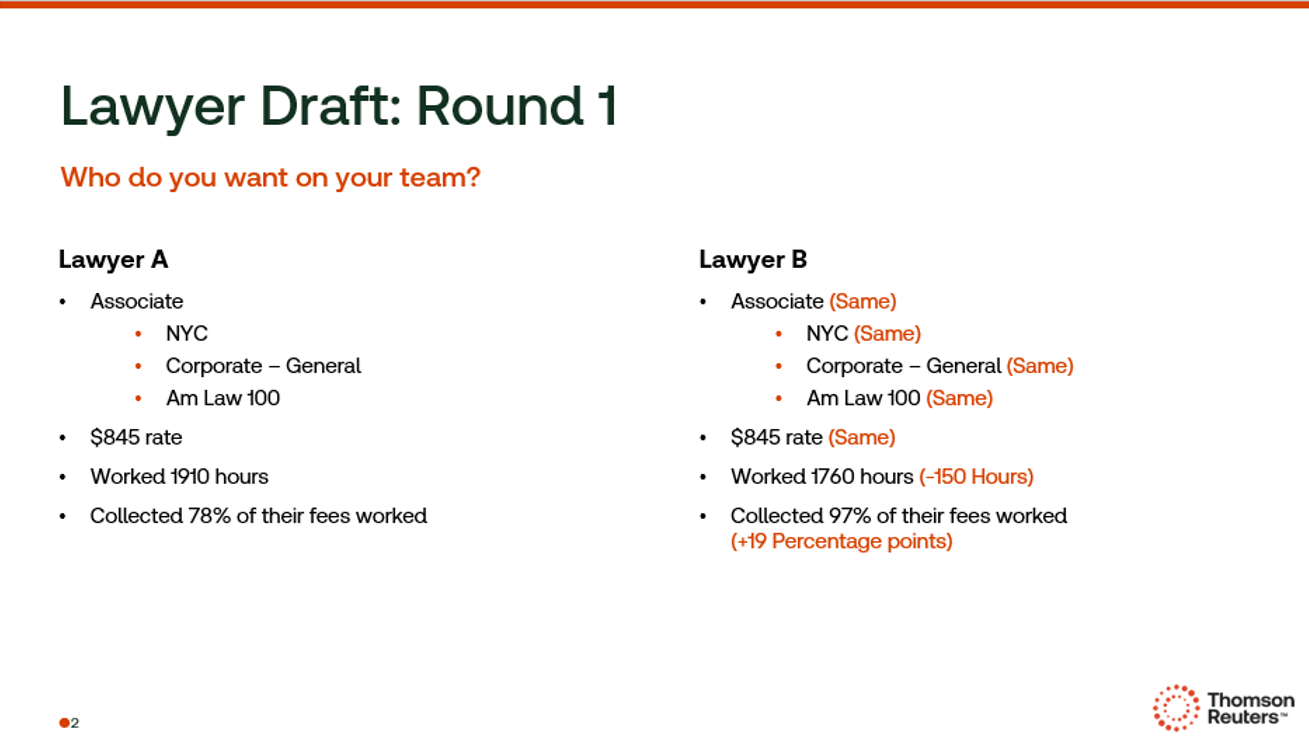

Round 1: Is productivity the same as hours worked?

First, we kicked off the first round by presenting two associates from the same class. Lawyer A had worked significantly more hours than Lawyer B, but Lawyer B had a higher collection realization rate. Following the initial presentation of the draft options, the audience was divided on their potential draft selection: supporters of Lawyer A argued that higher hours indicated greater dedication and potential for improvement in realization rates, while proponents of Lawyer B emphasized the immediate financial impact due to better collection realization.

After a spirited debate, one GM group selected Lawyer A, valuing the potential to improve realization rates, while the other group selected Lawyer B for the direct financial benefit. We then revealed the RPM scores: Lawyer B had a score 9% above replacement level, while Lawyer A had a score 2% below. The key takeaway was clear — hours worked are not the sole measure of productivity, and collections can significantly impact a lawyer’s economic contribution to the firm.

The GMs that drafted Lawyer A did so because they considered hours to be the primary area on which to focus with regards to productivity, however as I mentioned earlier, RPM is a profit-focused productivity measure; and under this lens, hours only matter if those hours lead to revenue generation.

While the argument that realization is out of an associate’s control is a fair one, we don’t see it like that exactly. Rather, we believe that realization is also a reflection of the quality of work that the associate provided which sometimes can lead to their partner discounting a certain amount during billing. Additionally, realization essentially captures the actual economic impact on the firm that the lawyer’s efforts have brought — bringing us, in turn, much closer to measuring what we consider productivity.

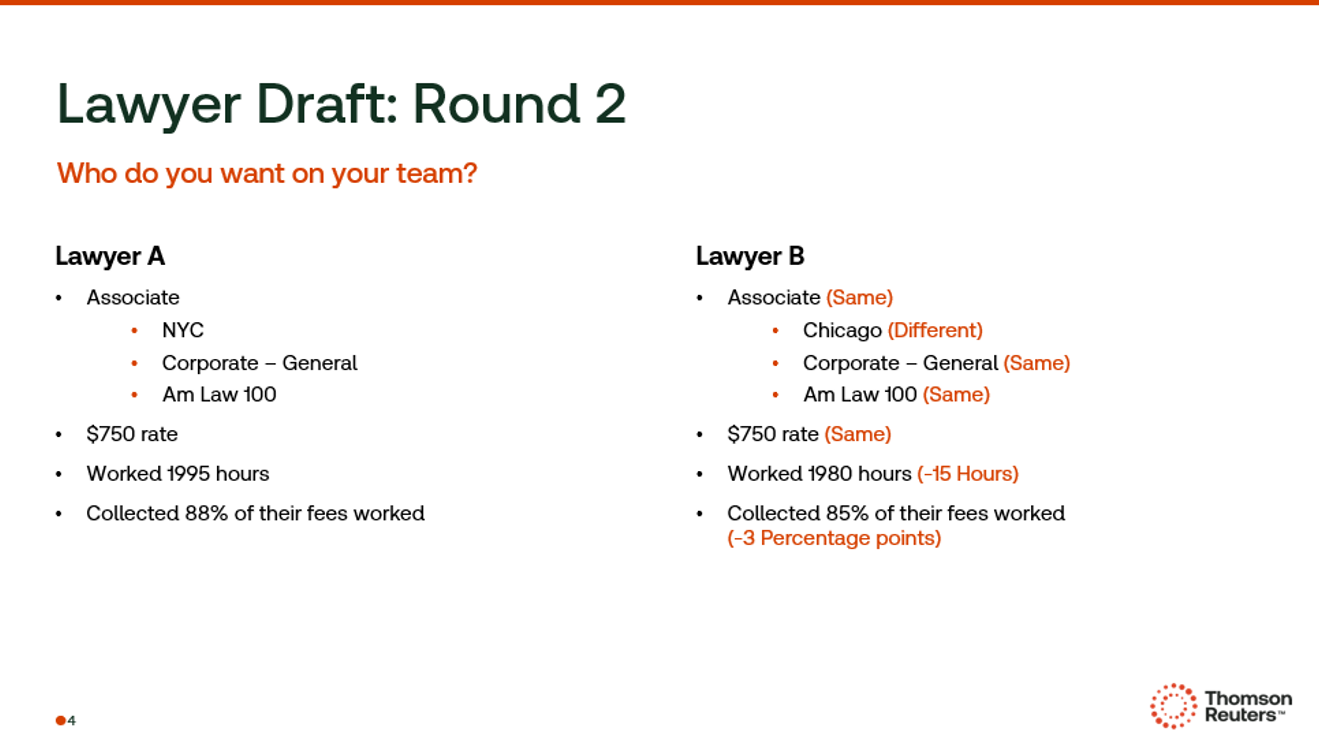

Round 2: Should productivity be absolute?

The draft continued as I presented another set of lawyers, both hailing from similar demographics, except for their office locations. (In this draft, Lawyer A came from New York City, while Lawyer B worked in Chicago.) Unlike the first round, however, their absolute productivity stats were nearly identical. They both commanded the same rate, while Lawyer A worked slightly more hours and collected a slightly higher percentage of their fees compared to Lawyer B.

With these much closer outputs, the audience and GMs leaned towards selecting Lawyer A, impressed by that pick’s marginally superior hours and realization rates. Then, however, one astute audience member pointed out a crucial detail: Lawyer A and Lawyer B were from different cities — one from NYC, the other from Chicago. This revelation prompted a quick re-evaluation of their choices. I could see the wheels begin to turn in the four GMs’ heads as they quickly re-evaluated what they had previously considered to be nearly identical stats. After a minute, both groups entered their pick: Lawyer B.

But why? Because despite similar rates, their performances were not identical when considering their respective markets. Lawyer A’s rate was nearly $100 less than the average for their peers in NYC, while Lawyer B’s rate was $40 higher than the average for their peers in Chicago. This meant Lawyer B had a greater financial impact on their firm relative to their market, despite a lower realization rate.

The key takeaway from this round, was that relative performance matters. We weren’t comparing Lawyer A to Lawyer B, we were comparing Lawyer A to Lawyer A’s peers and comparing Lawyer B to Lawyer B’s peers. Lawyer B’s financial impact in Chicago outweighed Lawyer A’s impact in NYC, showcasing that productivity should be measured in context, not in isolation.

Final rounds

Our session at LVNx concluded with additional draft rounds, further emphasizing RPM’s significance in evaluating productivity beyond mere hours worked and absolute measures. Each round highlighted how RPM could simplify the quantitative portion of talent evaluation, allowing law firms to focus more on qualitative attributes similar to the way that NFL GMs focus on non-measurable factors like attitude, coachability, and leadership. This balanced method ensures a comprehensive performance evaluation, aiding in better decision-making and talent management.

Overall, our workshop demonstrated that RPM is a profit-focused metric that measures an attorney’s relative output rather than their absolute output. By incorporating RPM into their evaluation processes, law firms can make more informed decisions, ultimately leading to better talent management and improved overall financial performance.

You can download a full copy of the Thomson Reuters Institute’s Relative Performance Measure (RPM) report here.