What can the defense industry teach lawyers about managing technology adoption in an increasingly AI-driven environment?

We all have tasks we tend to put off, like avoiding the dentist — perhaps because it is time-consuming or perhaps because it’s expensive or stress-inducing. Yet while we might get away with it for a while, it often comes back to bite us. Law firms, at this moment, are facing a similarly difficult choice when it comes to deciding how to approach generative artificial intelligence (GenAI).

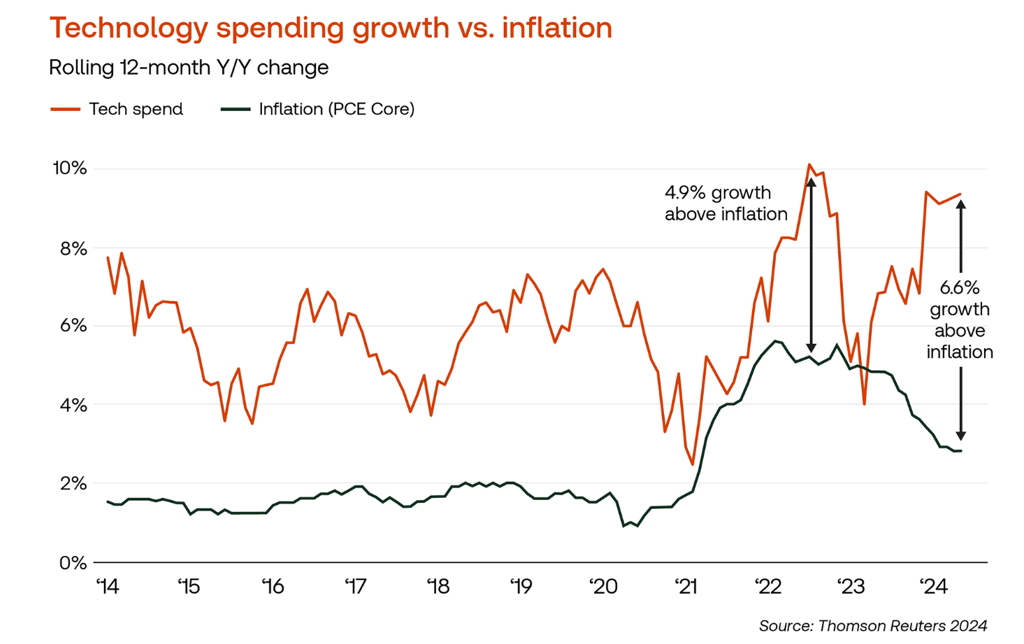

As reported in the 2025 Report on the State of the US Legal Market, law firms are in a transitional stage from both a business-culture and technology perspective. Tech spending versus inflation is at one of its highest levels in recent history and, unlike past spending spikes, it seems to be maintaining these levels. Fueling this massive spending is the technology’s potential. More than three-quarters (77%) of professional services workers expect the rise of AI and GenAI to have a high impact on their profession within the next five years, with 42% describing the impact as transformational, according to respondents to Thomson Reuters’ Future of Professionals report.

Conversely, the transition to this technology has the potential to be both challenging and costly. Many law firms may find themselves in a situation in which their tech budgets — already stretched by substantial investments in new technology — compel them to make budget cuts elsewhere. This may mean that a firm might use cutting-edge technology in some areas while other parts of the same firm retain outdated systems, and essential maintenance might be indefinitely postponed.

This scenario (and its consequences) is often referred to as “technological debt” or more simply, tech debt. As it was put in the 2025 Report on the State of the US Legal Market:

“The concept of technological debt involves incurring future costs due to expedient but suboptimal decisions made during a period of technological development or implementation. These decisions often prioritize quick delivery over thoroughness or a continuation of the status quo instead of a costly or risky evolution, leading to complications and increased maintenance efforts down the line. The longer this tech debt is held, the greater the cost becomes until it finally reaches a breaking point.”

While this problem can be incredibly destructive, its prevalence means law firms can draw lessons and strategies from other industry sectors that have successfully addressed similar issues and gain valuable insights into how to manage and mitigate tech debt effectively. Indeed, few sectors exemplify the challenges and solutions around tech debt as those of the defense industry.

The defense industry and tech debt

Despite the advancements in technology over the last couple of decades, many of the weapon systems prominently used today were developed in the 1960s and ‘70s. Many currently used military technologies date back to the Carter administration, if not further back. Although periodic updates to some systems have occurred, many still use parts that were obsolete by the end of the 20th century.

Raytheon, one of the largest defense contractors in the world, exemplifies this issue with one of their best-known products: a man-portable air-defense system (MANPADS) called the Stinger. First produced at the end of the Vietnam War, Stinger missiles still use parts designed in the 1970s and requires assembly by hand. While the device could almost certainly be improved with more advanced, easily sourced electronic parts, doing so would have required a major redesign and reauthorization process with the US military.

Raytheon continually delayed this process, managing to postpone it to such an extent that it was never actually completed. Instead, the company greatly curtailed production of Stinger missiles 20 years ago, focusing on small international orders and replacement parts. As a result, militaries around the world relied on Raytheon’s aging stock and a trickle of successor systems.

|

|

In February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Orders for systems that hadn’t been in production since the Clinton administration suddenly spiked at record levels while orders for existing systems saw their quantities multiplied by a factor of 10.

Now, Raytheon faces a crisis. The demand for Stingers has skyrocketed, with the U.S. Army placing an order for 1,500 units (at a cost of $687 million) in May 2022 and another order for $700 million dollars’ worth of units in 2024. Raytheon has found itself unable to fulfill these orders without spending years rebuilding their factory, a process that involves literally removing cobwebs from equipment locked in a warehouse for decades and recalling employees, now in their 70s, who worked on the original product lines.

Modernization of the system, pushed back continuously, is simply unpracticable. Raytheon is looking at a 30-month delay just to restart production on its new lines, and the relatively small order isn’t expected to be fulfilled until 2026. Given modern conflict, such a long timetable to receive such a relatively small quantity of equipment is a failure from a production standpoint.

Raytheon’s challenges are just one example of how the defense industry has felt the impact of tech debt and how failures to address it can lead to costly consequences. Yet while failures like this are commonplace within the defense industry and elsewhere, the high stakes of failure have driven organizations to employ a multitude of solutions for managing tech debt successfully.

And law firms may find many of these solutions just as applicable to their own services.

Collaboration and partnership

The defense industry often engages in collaborative initiatives, bringing together multiple stakeholders to address common challenges. This collaboration can involve joint research projects, shared training facilities, and industry standards for workforce development.

Similarly, law firms can join industry consortia, share best practices, and co-invest in training programs to build a stronger talent pool. Beyond talent benefits, partnering with technology companies can give law firms a first-mover advantage with new tech. For larger law firms, where experience is crucial, such partnerships can provide significant advantages and position firms as true partners rather than mere participants.

Developing a long-term technology roadmap

By developing a long-term technology roadmap, law firms can remain adaptable and ready to leverage emerging technologies. In the defense industry, for example, major projects such as the Joint Strike Fighter (F-35) and warships have tech roadmaps that stretch across decades and include multiple upgrades, with funding already allocated to them for these purposes.

Today, as the Future of Professionals report showed, a majority of professional service firm leaders said they expect a shortage of skilled labor, increasing regulations, and the rise of AI and increasing data volumes to have a significant impact on their professions. Thus, there has never been a time when having a clear technology roadmap has been of such necessity.

The legal industry stands on the brink of a transformative era that’s being driven by GenAI and other emerging technologies.

Any effective technology roadmap should contain a comprehensive vision that outlines upgrades, new tech adoptions, and alignment with business goals. This should span multiple years, covering immediate and future needs. Other aspects of a technology roadmap need to include risk mitigation and a prioritized budget that should contain enough flexibility to manage unexpected tech needs or opportunities. The roadmap should also be regularly updated to reflect tech changes and new market trends and business priorities.

Simulation, modeling and testing

An increasing standard within the defense industry is the use of simulation and modeling tools. Companies such as Lockheed Martin design in the digital space, using digital twins to model physical systems and test them virtually before assembling the first units in the real world.

This approach also may be relevant to the service-based industry, including law firms. Law firms already utilize simulation and modeling tools to predict outcomes of legal strategies and assess risk. Simulations of law firm office management already exist as a training method for young lawyers, similar to how business students run simulated companies in their courses. By advancing these simulations to model and test versions of their own firms, leadership can increase awareness of their firm’s limitations and potential.

Although this likely requires significant investment and effort, the process could help firms avoid making hazardous decisions while ensuring optimal resource distribution — thus, providing an edge among the competition.

Conclusion

The legal industry stands on the brink of a transformative era that’s being driven by GenAI and other emerging technologies. Law firms must recognize the critical importance of staying ahead of technological advancements in order to maintain a competitive edge.

By drawing lessons from the defense industry’s approach to their own tech debt, law firms can navigate these changes more effectively.