Systems engineering offers a robust framework for solving complex legal problems by breaking them down into manageable parts, ensuring integration and coherence in processes such as M&A due diligence and complex litigation

Systems engineering arose as a discipline in the late 1950s and early 1960s, concomitant with the beginnings of the space race. The discipline was developed for solving large, complex problems in the design of systems for which the tolerance of failure was slim to none.

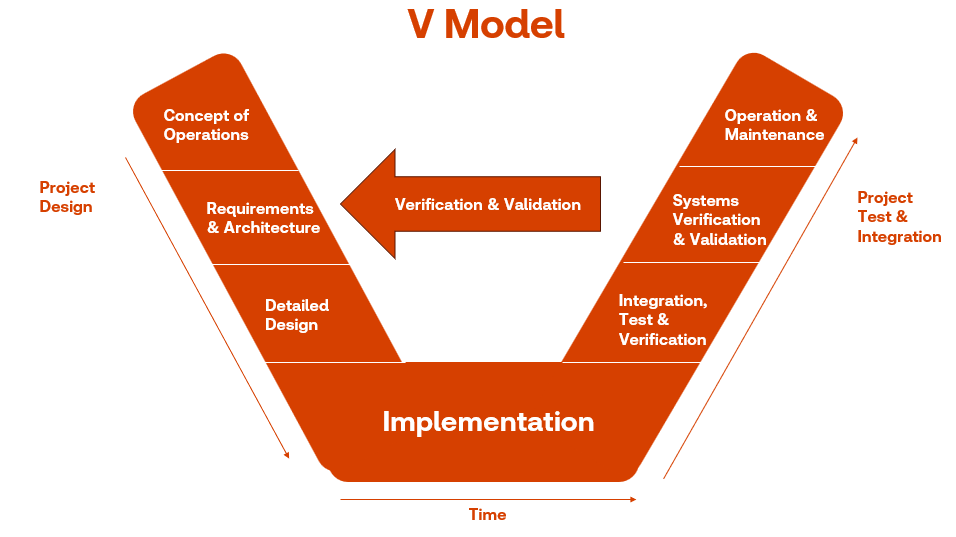

One of the most fundamental concepts of systems engineering is the V model that originated within the aerospace industry in the early 1980s. The idea of the V model is to provide a framework for complex systems analysis and problem-solving. As one would expect, the model is depicted in the shape of the letter V. The left-hand side moving downward includes key actions to be completed — such as analyzing what the requirements are, what needs to be accomplished, what the constraints are within the existing technology, what requires fixing, and what questions need to be answered.

The next step is to break down the problem into its various elements, which interestingly, is also a common practice of legal project management. This is the left-hand side of the V, and once it is broken down, those different pieces typically are assigned out to different teams, for them to examine and work on. Together, they form a team of teams.

At the bottom of the V is the time to gather and analyze the system in its entirety and to reassemble it into a new and coherent whole on the right side of the V. That whole is intentionally more capable, efficient, and resilient than what had existed before. The new system answers the mail for all the requirements, identifies all the interfaces and dependencies among the elements of the solution, and optimizes all the trade-offs. The integrated solution is thoroughly tested coming up the right side of the V.

Along the way, importantly, risk is retired, and margin is built up. What I mean by margin is the margin for error. The idea is that if something small goes wrong — in a deal, for example, if part of the analysis fails or something has been missed; or in a complex piece of litigation, if a witness’s testimony comes out the wrong way on a particular day — the margin for error is great enough that the system as a whole does not fail. Over several decades, I have found this to be a highly effective model of problem-solving in complex matters of law, regulation, and business.

Utilizing the V model approach during M&A due diligence

The V model can be a useful tool for demonstrating how systems engineering works in the in the legal field, for instance, starting with M&A. Often, lawyers work to close any disconnects between the various due diligence work streams arising from a potential M&A transaction. In a complex corporate transaction, responsibilities are broken down and actions assigned to separate teams for different diligence areas, including, for example, business development, finance, HR, intellectual property, and technology.

One of the ways that M&A deals can get off track is for those diligence streams to proceed in a disconnected or incoherent way. For that reason, it is important in managing a big deal to bring the teams together and make sure they are staying connected, so that all key interrelationships and patterns are identified.

Another example is identifying relationships between due diligence issues and findings and making an assessment of the target’s leadership. Observing a pattern in which a particular area is going errant repeatedly, it must be assessed whether the leaders for the target company in that area are really the right people to lead the business, post-acquisition.

A third M&A example is identifying the interfaces between the due diligence findings and deal negotiations. The terms and conditions, ideally, are going to be negotiated based on what the findings are during the diligence process. Sometimes they get disconnected. However, if diligence is tightly coordinated with the negotiation of terms and conditions, a better negotiation process emerges among those on the other side of the deal — company management and the company’s own board — resulting in a better set of deal documents.

Demonstrating systems engineering discipline in complex litigation

Another legal context in which to demonstrate the value of the V model is in complex litigation. Doing up-front legal analysis early is critical to understanding exactly what ultimately will be needed in order to prevail — whether that be a motion for summary judgment as a defendant, or in preparation for a trial — all before discovery is entered.

This is part of classic systems engineering, going down the left side of the V to understand all the requirements and what the objectives are before developing a solution. In civil litigation, which is what companies are predominantly involved in, this is typically done through discovery. Systems engineering is a good way of thinking about how to coordinate both defensive and offensive discovery — that is to say, what facts need to be extracted from the other side. It is perilous to assume in civil litigation that the case can be proved through something potentially received from the other side, so this must be undertaken with care.

Conclusion

Leveraging systems engineering in the anatomy of legal matters is a highly effective way of managing problem-solving. It tends to be most helpful in solving complex, interdependent, often technical problems; often over a longer-term time period, such as that involving major litigation or M&A deals.

Under this discipline, leaders need to bring their teams along to obtain optimal results. As a by-product of solving particular challenges, leaders will be building consensus, resilience, and ultimately common purpose within their organization.