Can law firms' two-tier partnership structures — featuring both equity partners and non-equity partners — not just endure, but be profitable?

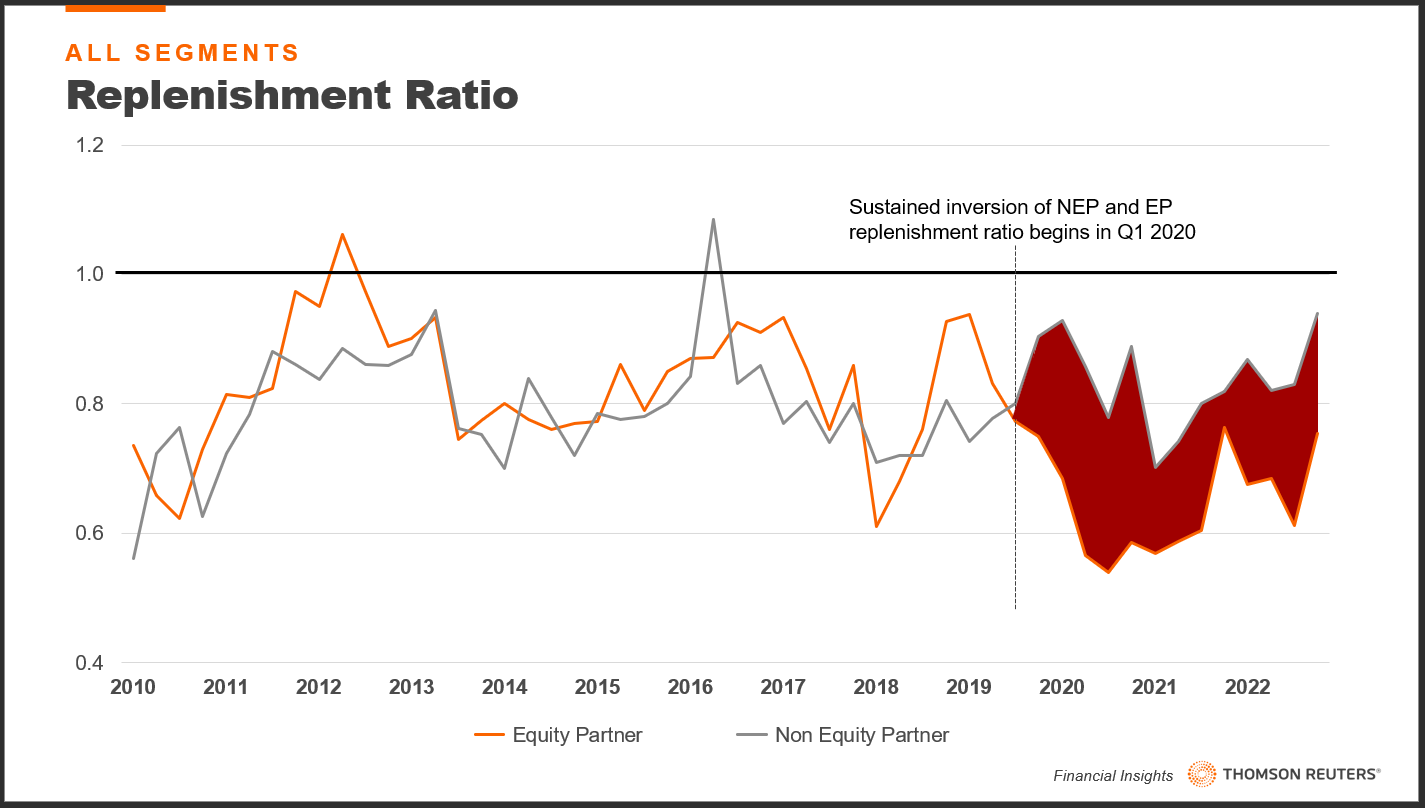

It seems that law firms may have settled on an answer to the question of whether they prefer to have a single tier or two-tier partnership structure. Since early 2020, the average law firm has replenished the ranks of its non-equity partner tier at a noticeably higher rate than it had for its equity partner tier.

Replenishment is a metric the Thomson Reuters Institute tracks to essentially account for timekeepers leaving a firm compared to timekeepers joining it. A replenishment ratio of 1.0 indicates a 1:1 ratio of timekeepers going in compared to those going out. Anything below a 1.0 indicates a shrinking timekeeper group.

It should be noted from the outset that both non-equity and equity partner tiers are in a long-term pattern of contraction. In fact, each tier only shows a single quarter of replenishment above 1.0 since 2010, with the tiers frequently trading places in terms of which is being replenished more robustly.

But since early 2020, a clear and often widening gap between the tiers can be observed. Replenishment of non-equity partners has hovered around 0.8. In contrast, replenishment of equity partners has varied relatively widely, dipping as low as 0.54 before recovering to 0.75 at the end of 2022. At that same time, however, non-equity partner replenishment jumped to 0.94, the first time that non-equity partner replenishment reached that high since 2016.

An increasing population of non-equity partners could be both a benefit and a detriment to law firms with two-tier partnership structures.

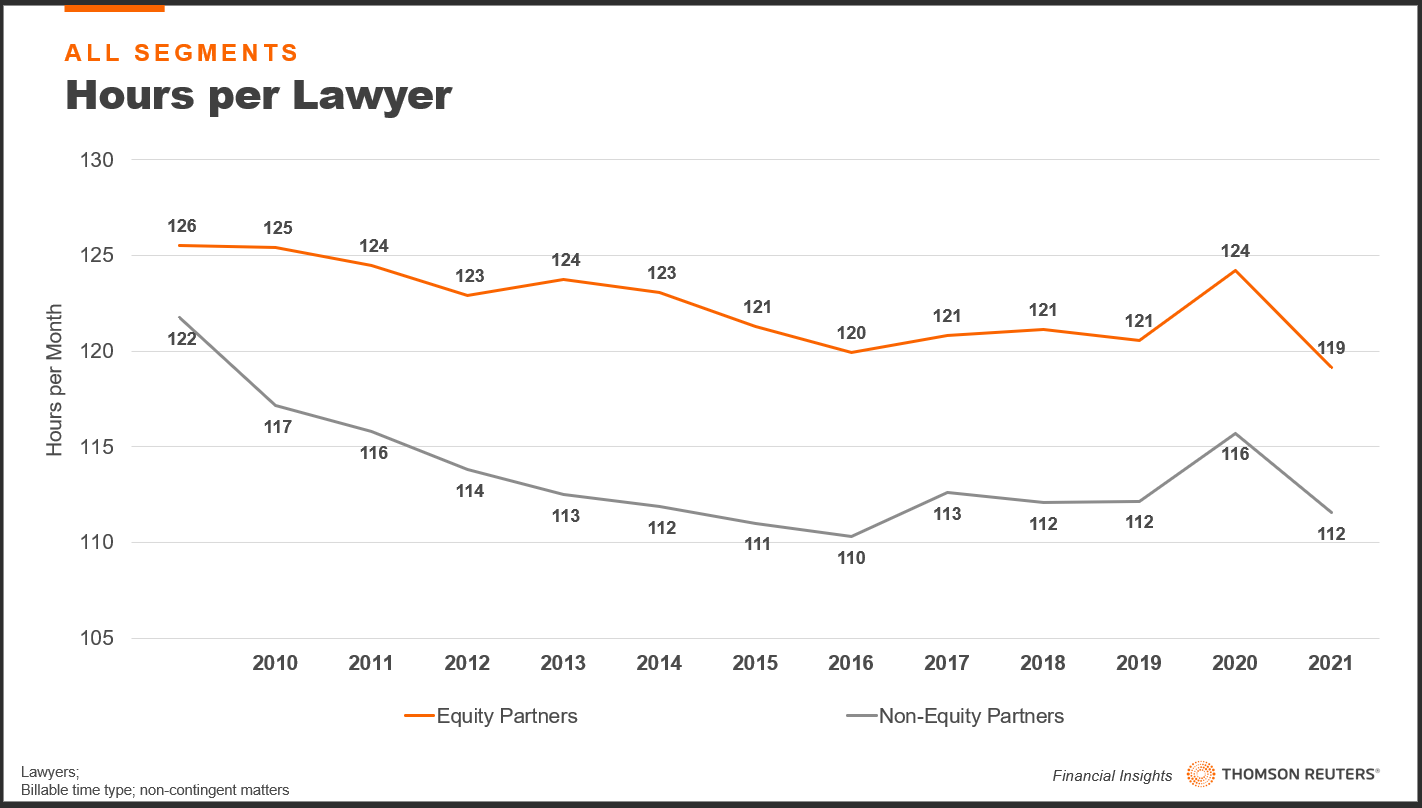

On the downside, non-equity partners naturally tend to bear little responsibility for business development and new client generation. Their contribution to the firm’s bottom line, therefore, depends on their productivity and individual profitability. One might hope that a lack of business development commitments would mean that non-equity partners have more time to devote to billable work. However, long-term patterns indicate that non-equity partners consistently underperform their equity partner counterparts in terms of hours worked per lawyer per month.

Going back to 2005, as far back as our data exists, there have been rare examples of non-equity partners approaching parity with equity partners in terms of productivity. However, the typical gap between the average equity partner and the average non-equity partner is between 7 and 11 hours per lawyer per month. Given the typical billing rates of these lawyers, that can translate into a sizeable gap in revenue.

On a more positive note, non-equity partners usually contribute to firm profitability in other ways. First, as the nomenclature would suggest, non-equity partners’ salaries do not vary based on firm equity, so they represent a fixed cost for the firm. In heady times, this can be a particular benefit as the payout to these partners will not vary as greatly as it would for equity partners.

In that same vein, the existence of a non-equity partnership structure creates an opportunity for law firms to offer a place of relative prestige — within the ranks of partnership — to lawyers who otherwise might not meet the criteria for full partnership. Many of these lawyers might be high performing in their own right and bring value to the firm in other ways, and they also might be at a greater risk to leave the firm if not for an upward option to non-equity partner status.

On a related point, the existence of a non-equity partnership tier can allow law firms to create upward mobility options for lawyers within the firm, while still closely protecting the denominator in the ever-important profits-per-equity-partner metric.

The upside of fixed-cost, non-equity partners, could potentially count against law firms during times of economic contraction, however. As these partners are a fixed cost, their relative share of firm expenses could grow as a percentage of revenue should the firm’s share of legal demand decrease, creating negative pressure on firm profitability.

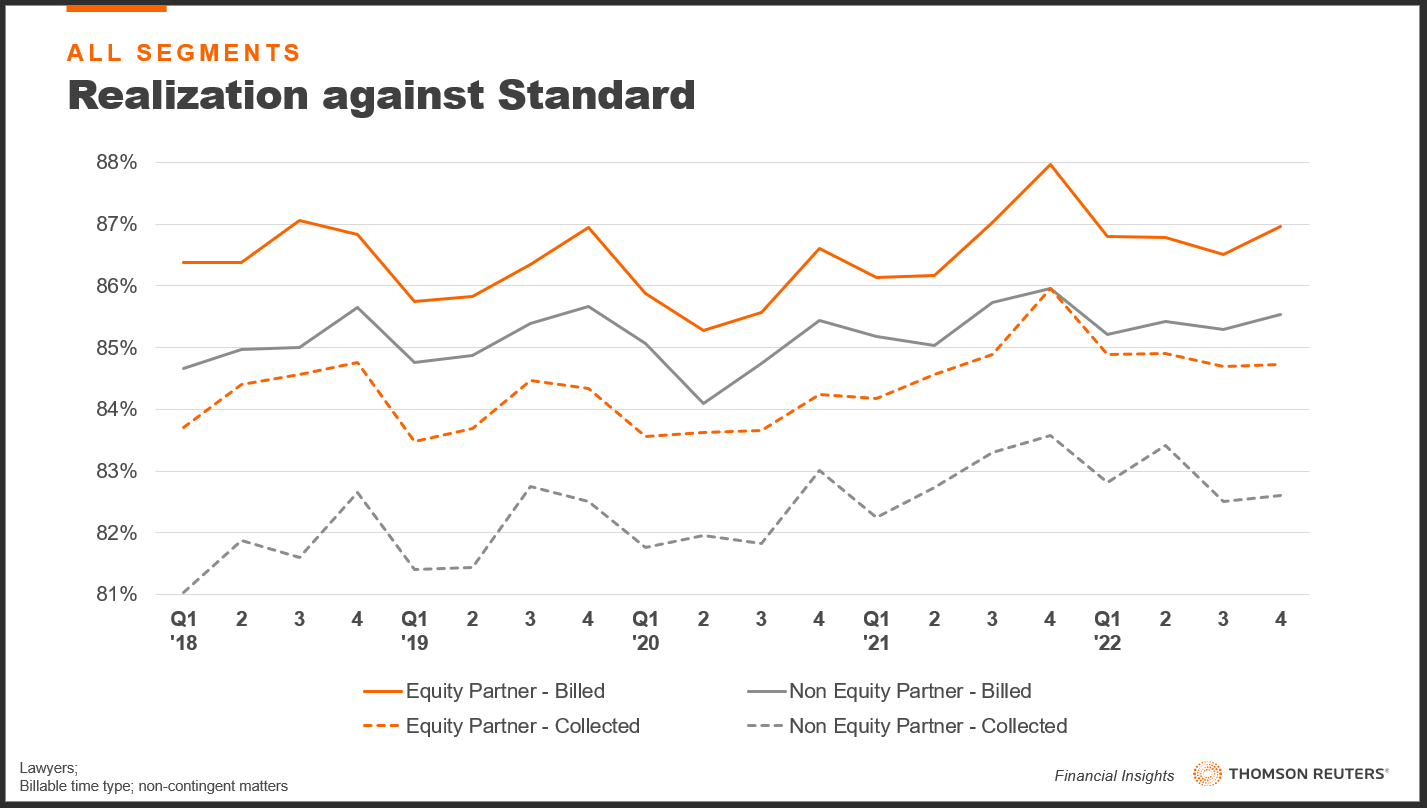

Non-equity partners may also create profitability pressure based on the realization percentage of their rates. As partners, non-equity partners typically command among the highest rates at the firm; perhaps not as high as equity partners, but certainly above those of associates. Looking at the realization of non-equity partner rates against their equity partner peers, it is quickly evident that non-equity partners are once again trailing the pack.

There is a persistent two-percentage point gap between the collected realization of an equity partner’s standard rate compared to a non-equity partner. This will likely have a detrimental effect on the non-equity partner’s relative profitability.

Some of this differential may be due to compensation structures and who has ultimate billing authority. It would be natural to suspect that, if an equity partner is the billing partner on the majority of matters and that equity partner’s performance is based in part on realization, the equity partner would be more likely to pass write downs or discounts on to other timekeepers, including non-equity partners. This could explain why non-equity partners also lag in terms of billing realization itself. If non-equity partners absorb a larger share of write-downs and discounts, this will predictably drive their billing realization downward, and their collected realization will decline along with it.

There is no clear answer as to whether a two-tier partnership structure is beneficial to a law firm. Indeed, there are myriad factors at play, well beyond those examined here.

Perhaps the clearest answer to whether a two-tier partnership structure is right for a law firm, is also a clichéd yet popular lawyer answer of It depends. If non-equity partner costs structures and profit margins, coupled with the potential to retain additional experienced talent, can work in a firm’s favor to outweigh the potential downside of a large, high-priced fixed-cost staffing tier, then it certainly can be beneficial.

Given the complexity of the question, however, this is far from assured.

This article was written in cooperation with Bruce MacEwen and Janet Stanton of Adam Smith, Esq.