Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) strategy is fast becoming a norm within corporations, although how those strategies are being implemented and managed may vary as numerous leaders with different roles within the C-suite may become involved.

When ESG emerged as a key business issue, it was something that businesses initiated in the broader context of employee engagement around the company’s core purpose and values, according to Hannah Peech, Head of the Corporate Affairs Practice at Odgers Berndtson. This insight came from a benchmarking exercise that Peech ran in 2017, which showed that the responsibility for ESG was typically co-owned by a company’s corporate affairs director and the procurement director.

When Peech conducted the research again in Summer 2020, the picture was even more fragmented. Many companies had expanded their ESG strategy, but there was not a clear trend in terms of which single executive committee director was responsible for ownership and delivery. Further, ESG had initially focused on the E — environmental issues such as carbon emissions and climate change. Over the course of the pandemic and amid the increased focus on diversity, social justice, and equity following the death of George Floyd, more conversation surrounding the S — as in social change, such as supporting and promoting individuals from underrepresented groups — came to the forefront. On the corporate front, diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), which had been a traditional agenda for companies’ human resources department, became an agenda for the board of directors.

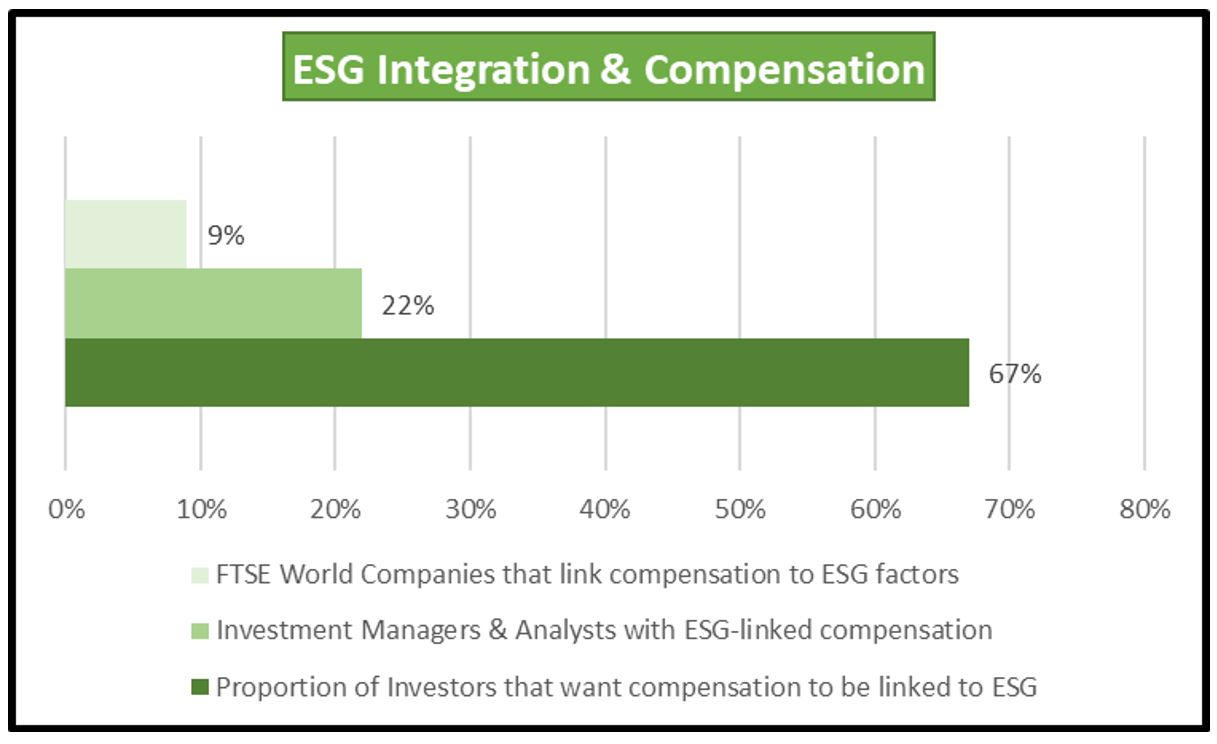

Shareholder activism around investors wanting ESG commitments that tied executive compensation to results and the growing public interest in these issues lifted ESG to the attention of the board. And this also elevated the significance of the G or governance part of ESG.

However, action on this front has been slower as very few organizations currently prioritized governance issues, even if shareholders demonstrate a desire for it. In fact, only 9% of the companies in the U.K.’s Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index (FTSE) link executive compensation to ESG issues, and only 22% of investments managers and analysts have their compensation linked to ESG outcomes, according to Andrew Archer, Partner & Head of ESG Advisory at Investor Update Market Intelligence. Even more problematic is that only 20% of corporations currently are aligned with the Paris Agreement on climate change, Archer adds.

Progress on ESG in the U.S. is a little harder to evaluate. As of July 2020, about 90% of the companies in the S&P 500 issue corporate sustainability reports, according to the Government & Accounting Institute. Further, most executives and the investment professionals who scrutinize their companies seem to agree that ESG programs reflect shareholders’ values, yet corporate boards —one of the most important constituency — remains unconvinced, according to a survey by McKinsey & Co. conducted in February 2020. Underscoring this, a 2019 PwC survey of more than 700 public-company directors found that 56% thought boards were spending too much time on sustainability.

According to Peech, company heads of ESG roles will now have to take on an influencer role that works well with the other leaders of those functions that own parts of the ESG platform and strategy.

Essential skills & abilities for C-level ESG leaders

To meet these essential requirements, most organizations that are creating full-time roles for ESG strategists are preparing to make an investment for the role for a distinct amount of time. As organizations see it, the main purpose of the full-time role is twofold: i) defining what ESG holistically means for the organization; and ii) creating a structure and execution plan to develop central operational processes that support the reporting, track the progress, and establish strategic, consistent messaging of the organization’s ESG progress and impact.

Because ESG terms, definitions, and reporting frameworks are evolving quickly and this is a new area of priority, candidates for these jobs often span other functions as well. More often than not, the new hires into these roles come from a corporate affairs background with a mixture of communications policy and government affairs, or from a strategy and investor relations background, according to Peech.

The most critical skill for new heads of ESG strategy is communications and being able to broadcast with transparency both internally to employees and externally to stakeholders, such as investors and customers. This requires the ESG leader to craft a concise narrative about where the company has been on its ESG journey, where it is now, how it measures success, and where the company plans to go over the next few years. Not surprisingly, that’s why you also see those individuals with an investor relations background leading the charge.

In addition, a track record of favorable outcomes when relationship-building with senior people is another crucial ability for ESG leaders. Embedded within this, of course, is the capability to both build trust and influence with the board and executive committee for the purpose of educating both groups and challenging their authority when necessary. Finally, a record of performance in leading transformation and cultural change, especially during a time of crisis or ambiguity, is another key indicator for success in the ESG realm.

Evolving the taxonomy of ESG

A current challenge for companies when hiring a head of ESG is the multiple frameworks of definitions and options that need to be traversed for the company to have effective measurement of the progress of its ESG strategy. Compounding the challenge is the recent and necessary focus on social impact and its own unique difficulty in measurement because it’s a little bit more subjective.

These definitions and taxonomies are evolving quickly, states Archer. He points out that there are excellent frameworks, such as the United Nations’ Guiding Principles Reporting Framework and the U.K. Modern Slavery Act, to point to as guides, but unfortunately, many organizations have been slow to adopt them.

Archer says he sees the current “convoluted” state of voluntary frameworks — including the recent initiatives by the World Economic Forum, the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation, and the CFA Institute — as a sign of positive movement in building ESG momentum. Indeed, the European Union now includes the principle of “do no harm” in its definition of sustainability, Archer explains. “According to the E.U. taxonomy, an economic activity can only be deemed sustainable if it’s not doing significant harm to any of the environmental objectives defined by the regulation,” he adds.

At the other end of the spectrum is industry self-regulation, a common approach taken in the U.S., which often results in rules that are based on the lowest common denominator. Archer points out, however, that the trend is indicating a different approach around ESG. “Unlike the most self-regulatory trends, we are observing the markets gravitating towards the highest level of disclosure rather than the lowest,” he notes. “In terms of capital allocation, this results in companies being rewarded for comprehensive disclosure.”