Can the Magnitsky Act become an effective tool to punish human rights abusers and lead to change among governments and corporations that do business with them?

The Global Magnitsky Act is the first global thematic sanctions regime that focuses on human rights. It has the potential to become an effective and consequential enforcement mechanism that can punish human rights abusers and foster behavioral change when its designations are acted upon and dealt with by all market participants.

But do human rights-related sanctions really work? Or are they merely citation-type labels that name wrongdoers but ultimately bear little consequence?

4 critical elements

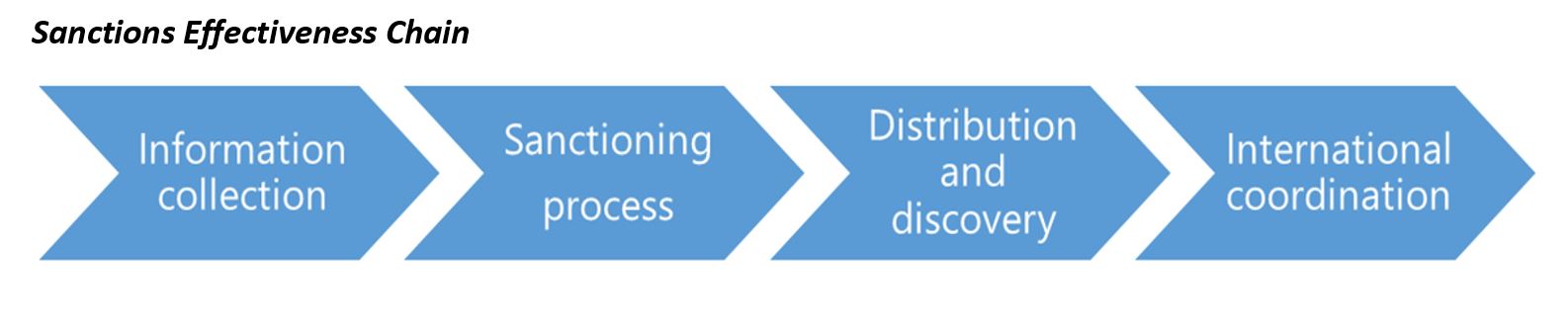

Looking at the current state of the Magnitsky Act, four critical elements correlate with its success and effectiveness.

First, information about human rights violation needs to be collected, verified, and submitted to governmental authorities. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), advocacy groups, and media outlets play an important role in this process. Once these violations are acted upon and sanctioned, the distribution and discovery work begins. Finally, international cooperation ensures that information is shared among jurisdictions.

Information collection phase

Significant work has been undertaken by the international community and by NGOs around the world to make human rights abuses public. Governments rely on the work of human rights organizations, as they possess sophisticated data analysis capabilities and digital platforms that collect, structure, organize, and visualize verifiable information about the parties involved. With an enforcement mechanism in place, the information collection and then the submission of this information to authorities has become a key element in the unmasking of human rights abusers.

The NGO Human Rights First, for example, has been influential and active in submitting verified information to the Global Magnitsky Act Sanctions program. Roughly one-third of the 340-plus names on the U.S. Global Magnitsky Act have been submitted by Human Rights First.

Distribution & discovery

For a human rights-related sanctions program to make an impact, however, the process of information submission needs to be expanded, and the granularity of information needs to be enhanced.

Government authorities do not possess the capabilities alone to build complete ownership structures, which are included in the U.S. Global Magnitsky Act, if an entity is 50% or more owned by a sanctioned entity. But data providers and research think tanks possess specialized resources and capabilities to collect this information.

Conducting due diligence using AI-Powered Adverse Media

While companies and financial institutions still rely on internet search engines such as Google to conduct due diligence, this often produces mediocre results. First, Google produces a lot of output that is time-consuming to sort out; also, search engines uncover many false positives, which often include multiple hits for the same content. It can be difficult to determine true adverse events and verify the identity of a subject. The results also might miss significant risks not contained in mainstream news sources.

Second, Google is a consumer-oriented search engine, and investigators can miss vital content that might be buried in databases that traditional search engines cannot access.

Third, criminals can pay Google or other service providers to delete information from websites, such as news aggregating sites. Search engine suppression is a tactic that includes creating positive content so that negative content is harder to find.

Adverse media solutions can play an important part in uncovering human rights abuses, as they are powered by artificial intelligence and can include proprietary databases and other criminal records — such as records from local law enforcement authorities — that would not be visible in a Google-type search.

International coordination

With the Magnitsky Act now passed into law in every major Western democracy, it will be difficult for actors to move assets to other destinations because many will have similar legislation is in place and more financial institutions are acting under a unified set of rules. To maximize the effect of a global human rights sanctions program, however, international coordination of sanctioned entities is important.

If an individual is banned under the U.S. Magnitsky Act for human rights violations, it should create a process of reciprocity in which independent due diligence is conducted on the same individual in other parts of the world. While this type of information-sharing would not guarantee the sanctioning of that individual or enterprise, at least the case would be heard.

Reciprocity should most certainly include all actors sanctioned for serious human rights violations, like crimes against humanity, genocide, torture, and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

If other offshore banking havens also implement Magnitsky Act-type sanctions, then significant progress will be made. As part of the U.K. Magnitsky legislation, for example, British overseas territories have followed the lead of the U.K. and implemented similar legislation. Guernsey, Jersey, Gibraltar, and the Cayman Islands will freeze all accounts in their jurisdiction if an entity is sanctioned in the U.K.

Effective tool

Overall, the Global Magnitsky Act has shown it is an effective tool in combating human rights violations and corruption overall, and there are many examples where behavioral change was achieved.

For example, Pastor Andrew Brunson was released after sanctions were issued against Turkish government officials, and then removed after the pastor was released. And the sanctions against Israeli businessman Dan Gertler, who amassed a fortune through corrupt mining and oil deals, had an indirect effect on the companies that were doing business with Gertler. For example, the Republic of the Congo lost $1.36 billion in revenue from the sale of underpriced mining assets; and mining company Randgold cut ties with Gertler after he was sanctioned.

Unlike previous sanctions that targeted countries like Iran or North Korea, it is now possible to go after human rights violators individually, even if they are from country that is considered to be an ally. This puts pressure on business partners of sanctioned entities, like in the Gertler case, as they face a risk of being sanctioned as well.

If the visibility of abusers and their business partners is increased and if Western democracies are aligned in their fight against those who undermine human rights, then those who are exploited for financial gain clearly stand to benefit — as does the integrity of supply chains and the financial system overall. Who wants to do business with a human rights abuser after all, if the abuse will become known to the public?

The risk of conducting business with a sanctioned individual or company is measured not only by regulatory standards and enforcement mechanisms — such as the Global Magnitsky Act — but also by this information becoming public for everybody to see and to read. Ultimately, this might be the greater risk. Publicly traded companies could face public outcry and a risk re-evaluation from investors and shareholders if such alliances are uncovered, ultimately resulting in loss of revenue. There is a significant reputational risk that leads to financial risk when such violations occur.

Indeed, creating transparency is very likely the biggest driver of behavioral change in human rights-related wrongdoing.