Unions and workers may like the United States' new 10% tariff on aluminum. China, Canada and end consumers may not.

United States President Donald Trump announced March 1 he will instate a tariff of 10% on all aluminum imports regardless of origin. Fully aware of the political ramifications of his decision, he tweeted the next day, “Trade wars are good, and easy to win.”

The president’s choice represents a more extreme option among the recommendations prescribed by Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross upon concluding the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 Section 232 Investigation on February 16, 2017. The stated intention of Ross’ proposals is to boost domestic production to meet 80 percent capacity in the coming year, up from 48 percent in 2017.

The stock market ticked down in response to the announcement, with industrial equities seeing steeper declines than the market as a whole. Shares of Boeing and automakers were particularly hard-hit, with investors quivering at the possibility of retaliation that would lessen demand for U.S. exports.

The Section 232 Investigation

The impetus for the Section 232 investigation is widely understood to be the U.S. administration’s desire to retaliate against Chinese national subsidization of industry. Proponents of enacting the section argue that China is flooding the market with cheap aluminum, weighing on global prices.

Secretary Ross concluded from his investigation that aluminum imports do indeed “threaten to impair national security,” the criterion for the invocation of Section 232. (See the full findings of the aluminum investigation on the Department of Commerce website.)

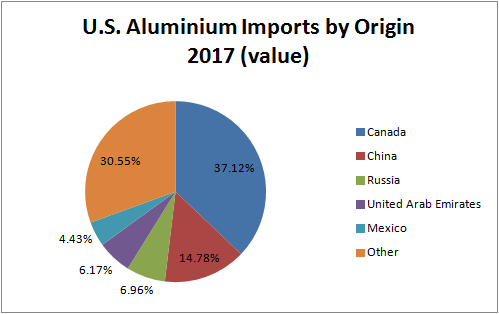

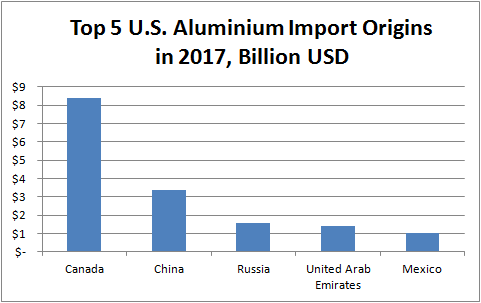

Ironically, the plurality by country of U.S. aluminum imports is not from China, but Canada, with 37 percent of total imports by value in 2017 and the majority of unwrought aluminum imports (the largest import category). Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland has expressed her opposition to the tariffs, stating Canada will respond with measures defending their own interests.

The scope of the investigation and recommendations includes primary and downstream products only. With respect to aluminum , there is no indication that imports of bauxite, alumina, scrap, powder or flakes will be affected. Tariffs will cover 95 percent of 2017 imports by value within aluminum (non-ore) products, a share valued at US$21.6 billion in 2017.

What constitutes success?

The official aim of the tariff is to boost domestic production, moving output to 80 percent from the current level of 48 percent. The difference between 48 percent and 80 percent of capacity amounts to an increase in output of just 669,000 tons, an amount equivalent to 13 percent of the volume of unwrought aluminum imports and less than an estimated 8 percent of total aluminum imports in 2017. An increase in aluminum capacity of 669,000 tons would provide approximately 1,000 jobs (for perspective, a net 200,000 jobs were created in the U.S. in January 2018).

An inevitability of the tariff is higher prices for both domestic and imported aluminum products. An increase in the price of aluminum is imperative to boosting domestic production, as higher prices would be necessary to make domestic manufacturing worthwhile to producers.

To make a long story short, the best-case scenario resulting from Section 232 is a relatively modest increase in domestic production and an accompanying boost in prices, paid for by consumers and downstream industry. The worst-case scenario is an increase in prices without the very slight economic lift that 1,000 new manufacturing jobs would provide. Either way, U.S. businesses and consumers will pay more for aluminum very soon.