Professionals in the legal, tax & accounting, and risk & fraud industries largely agree on the ethics of AI — but when a recent report finds some parties are more willing to allow AI to dispense advice than others, misalignment can easily follow

By and large, those working in professional services industries view the oncoming rush of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) in a positive light. Indeed, 78% of respondents from the legal, tax & accounting, risk & fraud, and government industries said they believe AI to be a force for good in their profession, according to the 2024 Future of Professionals Report from Thomson Reuters.

This may be particularly surprising given that many of these industries have a reputation for being risk averse. It may appear that AI’s potential has conquered even the most skeptical of industries.

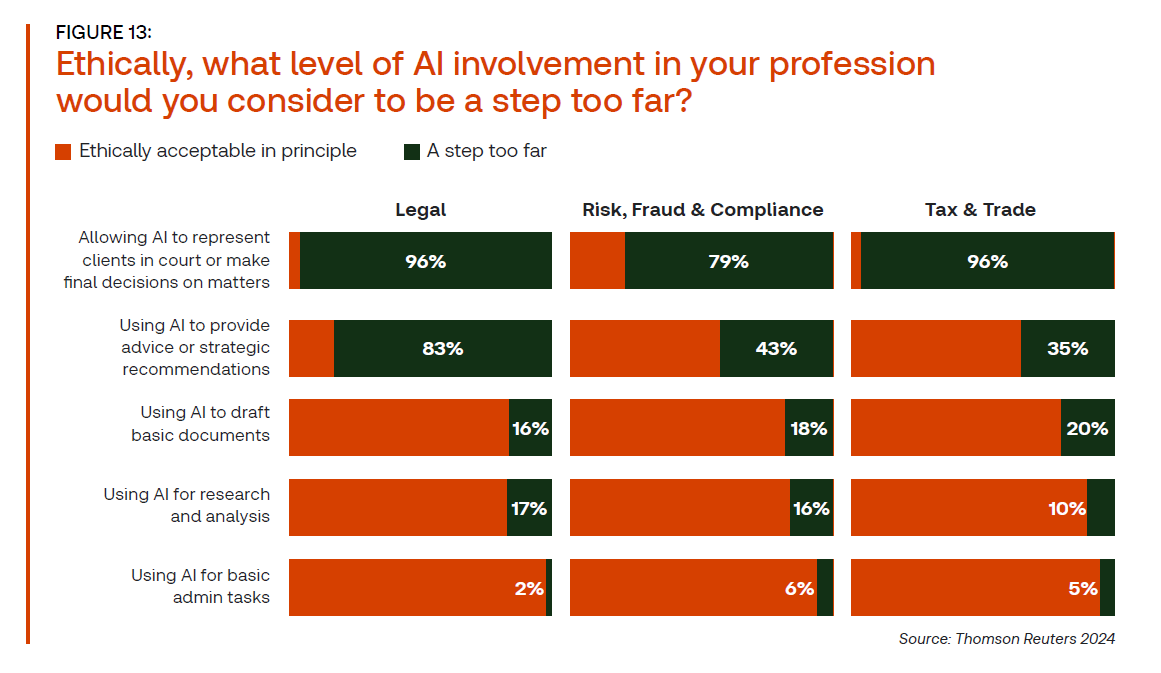

At the same time, however, this does not mean that these professionals want GenAI applied universally. According to that same report, there are some activities that professionals see as a step too far in applying AI. Using AI for basic administrative tasks, for instance, is a widely accepted use case; however, allowing AI to make final decisions on important matters is considered a step too far.

Even within this framework, there is a gray area. Notably, there are stark differences among professionals in different industries about the utility of AI to make strategic recommendations. And particularly for the legal industry, the differences could mean that clients are more willing to push boundaries than are law firms themselves.

What’s a step too far?

GenAI is increasingly being baked not only into industry-specific tools like legal and tax research, but also into general business tools like those of Microsoft, which introduced its AI tool, Copilot, into Office 365. Yet, given that ChatGPT was still released less than two years ago, professional services organizations have needed to quickly respond with policies and procedures surrounding GenAI’s use — and in some cases, they have not had the ability to do so.

Survey data from April, for example, estimated that only about one-quarter of these organizations had either a stand-alone GenAI use policy or a larger technology policy that covered GenAI. While this percentage has surely increased in the intervening months, the fact remains that many professionals are left to their own devices about what is a proper or an improper use of GenAI.

And as it turns out, different types of professionals have different opinions about where the line should be drawn as to whether one should ethically use AI or not.

When asked what level of involvement would be a step too far for AI, most respondents agreed that using AI for administrative tasks, research and analysis, and drafting documents would largely be okay. On the other hand, most disagreed with allowing AI to represent clients in court or make final decisions on matters (notably, however, 21% of risk & fraud professionals thought even this would be reasonable).

The areas in which industry professionals differ, however, is in allowing AI to provide advice or make strategic recommendations. Only 17% of legal professionals said they thought allowing AI to provide legal advice would be ethically acceptable; but among risk & fraud professionals, 57% said they believe using AI to provide advice or strategic recommendations is acceptable — and among tax & trade professionals, that figure rises to 65%.

This disconnect could come from what these professionals see as the nature of advice. Legal has long been a relationship business. And there’s a reason that when corporate attorneys are asked what they want from their outside law firms, it’s quality and communication above all else. As a result, it’s no surprise that when legal professionals have been asked about their greatest fears concerning AI in the profession, that loss of the human touch regularly tops the list.

“AI is just that — artificial,” said one United Kingdom-based law firm partner told researchers of the Thomson Reuters Institute’s Generative AI in Professional Services report earlier this year. “There are well-known examples of generative AI citing cases which do not exist. People need people to understand them and their needs, not algorithms. AI could be used for simple administrative tasks, but not for substantive legal work and generating documents.”

“AI is just that — artificial. There are well-known examples of generative AI citing cases which do not exist. People need people to understand them and their needs, not algorithms.”

— UK-based law firm partner

On the other hand, the risk & fraud and tax & trade professions, while still heavily focused on relationships, also tend to be heavily analytically focused. Naturally, this means that the nature of advice is different — more quantitative, less open to interpretation, and thus potentially more able to be automated.

“I am excited about the support function to human decision-making,” said one New Zealand-based corporate risk manager. “In the electricity industry, we have a number of functions such as creating switching steps for switchgear which still rely on numerous human decisions, which naturally expose us to human failure. In this task, failure then relies on another human defense to notice and not apply the incorrect steps.”

It also doesn’t hurt that both the tax and risk professions are facing a talent crunch, and simply need more resources to provide advice — a resource such as GenAI. One professional staff at a United States tax firm predicted: “It’s going to solve the problem of not having enough talent entering the industry by enabling massive efficiencies in accounting preparation, review, and client service.”

What it means for the future of legal advice

Naturally, this could represent a conundrum for those giving legal advice, both attorneys at law firms working for corporate clients as well as corporate lawyers working for internal stakeholders. Even if legal professionals don’t see AI as an ethical source of strategic advice, it could be that the ultimate clients they’re serving are becoming more accustomed to GenAI for that usage.

Indeed, according to that Generative AI in Professional Services research, corporate risk & fraud professionals in particular use GenAI at a higher rate than other industries, with 32% saying they’ve used public tools such as ChatGPT for personal use and 18% saying their departments use it on a wide-scale basis. Not only that, but those corporate risk & fraud professionals that are using GenAI are doing so frequently — nearly half (45%) of risk & fraud GenAI users say they are doing so multiple times a day.

“It’s going to solve the problem of not having enough talent entering the industry by enabling massive efficiencies in accounting preparation, review, and client service.”

— US-based tax firm professional

For legal professionals then, it primarily means having a conversation: If their clients want GenAI to not only be used for back-office work, but to be integrated into the advice-giving process, how will they handle that? At a time when few organizations have defined policies around GenAI usage, it may be helpful for firm leadership to write standards and guidelines for the organization’s approach to GenAI, specifically around dispensing both business and legal advice, with special attention to when it is appropriate and when it is not.

There is also the scenario in which legal professionals are competing against AI to provide advice. Indeed, one common sentiment in our research is that corporate clients don’t want their law firms to simply regurgitate findings from GenAI. Clearly, corporations have the same access to the same tools, so they want their law firms to go above and beyond in adding strategic thinking. Law firms in particular should be mindful of this and aim to be strategic in everything they do. In a world in which information is more easily disseminated, it is in the skill of critically applying AI output that will set lawyers apart.

In a GenAI-enabled world that still may seem like the Wild West at times, everyone will have different opinions as to where AI is applicable and where it is not. For legal practitioners to be most effective, however, it will be important to understand where those differences of opinion occur, and make sure they’re communicating with clients to find the right ethical balance for all parties involved.

You can download a full copy of the Thomson Reuters Future of Professionals report here.