A state court judge in Kansas wanted to figure out how to reach more of his family law docket and prioritize the true problem cases. During a panel at the AALL conference, he explained how he partnered with NCSC and Colorado Law School to build a technology aid

CHICAGO — With modern legal technology solutions, the goal is to help lawyers do their job more accurately, quickly, and in greater service of the client. This comes in a number of different forms, with innovations in legal research, contract and transactional management, discovery, and more helping lawyers conduct their work in a better way.

However, the current focus of legal innovation also begs an interesting question: How do you help those that you might not even know have a problem?

Judge Keven M.P O’Grady of the Kansas 10th Judicial District, in Johnson County outside of Kansas City, was running into this exact problem. A former family law attorney himself, Judge O’Grady’s docket primarily deals with family law cases. And like many courts in the US, his court has dealt with capacity issues, a rising case load, and notably, dissatisfaction within the court itself. In particular, he noted that because court systems are designed to deal with the worst cases, those cases that had a relatively simple problem at their core were still subject to complex solutions.

“As a legal system, since we’re worried about the problem cases, we’ve set up all these hurdles and hoops for people to jump through,” Judge O’Grady explained. “It’s no surprise that people who come in for a simple process begin to resent the legal system.”

A solution can be found through technology, however, as he and University of Colorado School of Law professor Staci J. Pratt told the crowd at the 2024 American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) conference. And by providing a new way to traverse the court system, Judge O’Grady’s court not only has engendered higher satisfaction for family law litigants but has created a vital data repository that can aid the court in identifying key issues to confront for future projects.

The ‘triage’ line

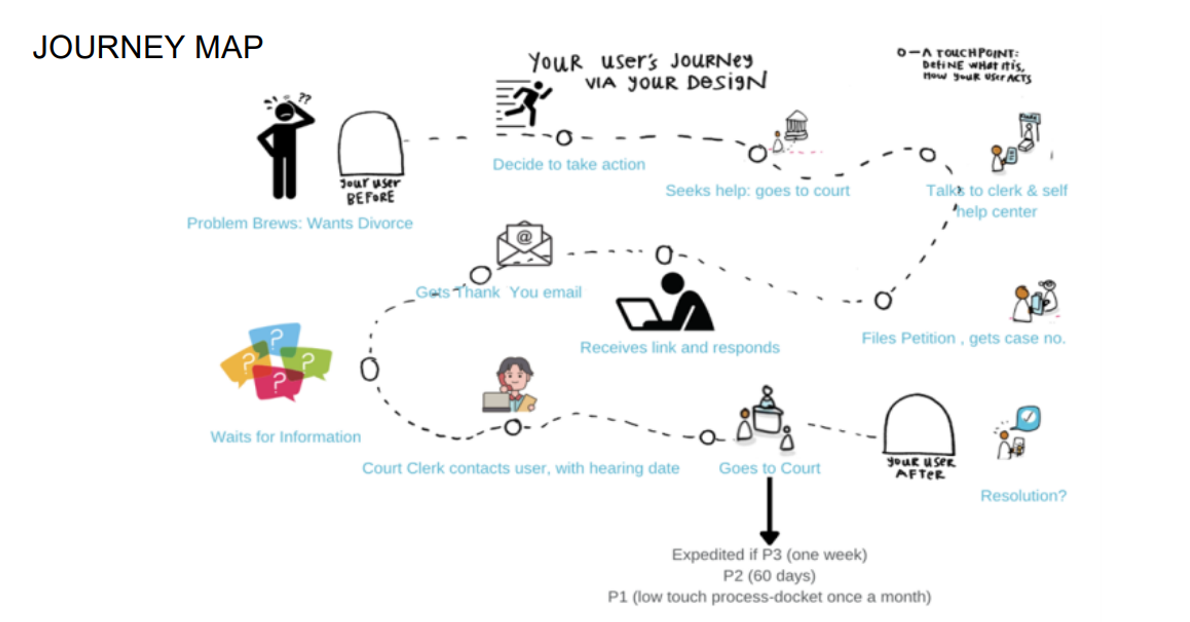

As explained in the AALL conference session Advancing A2J: Building Collaborative Partnerships with State Courts to Improve Usability of Judicial Legal Applications for All Users, Judge O’Grady partnered with the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) to develop a “triage” system. Similar to a medical triage that determines the level of care an incoming patient should receive, Judge O’Grady’s court sought to sort family law litigants into three categories: Pathway 1 (low-touch, fast-track); Pathway 2 (standard litigants); and Pathway 3 (high-conflict litigants). This way, he said, courts are “using our time on cases where time needs to be spent.”

“The idea is that we want to change the focus of how we’re handling cases from the process and the judges… to focus it on the children and families,” he continued. “What we found is, by focusing on the family and what the family needs rather than what the court needs, we are increasing litigant satisfaction.”

The process to get to this point was not an easy one, he explained. First, the court engaged community feedback — from professionals such as lawyers, therapists, and psychologists — to determine what problems litigants actually need to fix. Following the creation of a series of neutral questions to ask new litigants, the court then tried to triage using paper forms, but soon found they didn’t have the resources to actually analyze the data they received back. Then, the court tried to build a website, but the process was too difficult for court IT staff, and many vendors’ prices were exorbitant. Then, after finding a vendor in Australia who could do the work, the vendor went bankrupt shortly after the site launched.

During this process, however, Judge O’Grady’s court found that it wasn’t alone in trying to innovate this process. The NCSC relayed that similar innovation programs were taking place across the country, from Massachusetts to Florida. In particular, NCSC connected Judge O’Grady with a team at Arizona State University, which helped re-design the intake forms.

The result was a formalized journey that integrated technology and process in a way that was aimed at making the family law journey as easy as possible for litigants.

Iterating and updating

Those looking to emulate systems similar to what the Kansas court did will find that very few technologies arrived fully formed. To perfect his court’s system, for example, Judge O’Grady turned to Prof. Pratt and her team at the University of Colorado School of Law. Pratt helped coordinate a review of the triage system using Human Centered Legal Design, a system spearheaded by Margaret Hagan, Executive Director of Stanford Law School’s Legal Design Lab.

At the core of the review, Pratt said, is that litigants — and especially pro se litigants — need to understand the questions that they’re answering. “The core of usability analysis is listening to users. That means testing the tool with real people,” she explained. “The reality is, however, how you decide to answer your questions will have a consequence on how your case is treated.”

With this in mind, the U of Colorado Law team set about conducting moderated observation-based usability analysis — or in other words, interviews with a diverse set of potential users to see how they would use the triage tool. The interview team asked respondents a series of questions based off usability heuristics developed by usability pioneer and co-founder of Nielsen Norman Group, Jakob Nielsen. These questions queried users’ initial observations, the takeaway or understanding from the first page, if users can describe the purpose of the tool, and more. Pratt also said that these interviews don’t need to be labor-intensive, noting that her team found key pain points through just eight interviews.

From there, Pratt’s team provided recommendations, such as providing a clear road map with next steps after filling out the form; directing users to a status bar during the question process; avoiding legal jargon; and incorporating trauma-informed design for sensitive issues.

But the improvements won’t stop there, Pratt and Judge O’Grady noted. For court systems looking to undertake a similar process, Pratt emphasized that these designs are meant to be iterative. “You never solve the problem, but you help make it better,” she added.

And for any of these improvements, they both emphasized that the work must remain user-centered, with litigants at the forefront. Pratt said that for similar situated court systems and law librarians looking to follow their lead: “Make sure users’ needs and goals are your lodestar for decision-making.”